Deadlocks in Distributed Systems: Detection, Prevention, Recovery

In this article, we explain what distributed deadlocks are, how they differ from blocking and slowness, the main types of distributed deadlocks, and practical strategies to prevent them in real systems.

What Is a Distributed Deadlock?

In a single-process or monolithic application, deadlocks are ugly but predictable. In distributed systems, they are 'quieter', harder to detect, and far more expensive.

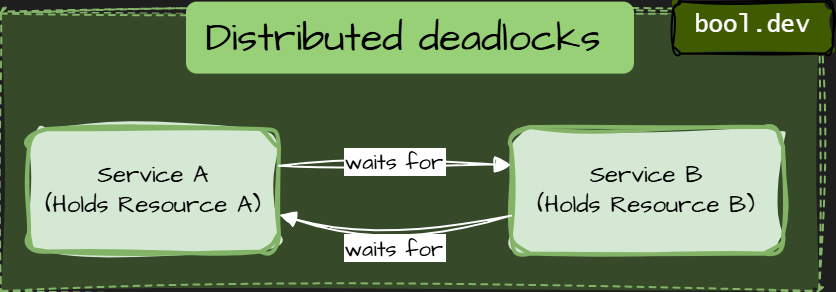

A distributed deadlock occurs when multiple independent services wait for each other, preventing any of them from moving forward. Each service is healthy on its own. The system as a whole is stuck.

This makes distributed deadlocks dangerous:

- There is no single place where the deadlock "lives".

- Logs look normal, services are up, CPUs are idle

- Retries often make things worse

- Recovery may require manual intervention

Most teams do not explicitly design for deadlocks. They appear later under load, during partial failure, or when a new service dependency is introduced.

Note: Not all waiting is a deadlock. Deadlock means no possible progress, not just slow progress.

Key characteristics of distributed deadlocks

- Services are healthy, but workflows stall

- Retries increase the load but do not unblock anything

- Timeouts cause rollbacks that block other operations

- Manual restarts “fix” the problem temporarily

- These signals will repeat across all deadlock types we discuss next.

Example of distributed deadlock

Coffman Conditions under which a deadlock occurs

Note: A deadlock can occur only if all four conditions hold.

1. Mutual exclusion

Only one participant can hold a resource at a time.

In distributed systems, this includes:

- database row or table locks

- distributed locks (Redis, etcd, ZooKeeper)

- exclusive access to external APIs

- single-writer guarantees

Nothing unusual here. Mutual exclusion is standard.

2. Hold and wait

A participant holds one resource while waiting for another.

This is where distributed systems start to hurt.

3. No preemption

Resources cannot be forcibly taken away.

In distributed systems:

- You cannot safely “steal” a DB lock

- You cannot interrupt a remote call cleanly

- You cannot roll back another service’s transaction

Once a service holds a resource, the system must wait for it to release it voluntarily.

4. Circular wait

A cycle of dependencies exists.

This is the condition everyone knows, but rarely sees clearly in distributed systems.

Types of distributed deadlocks

Resource-Based Deadlocks

Resource-based deadlocks are the most common type of distributed deadlock. They happen when services hold exclusive resources and wait for other resources owned by another service.

What counts as a “resource” in distributed systems

In practice, a resource can be:

- Database rows or tables.

- Distributed locks (Redis, etcd, ZooKeeper).

- Files or object storage handles.

- Rate-limited external APIs.

- Single-writer business invariants (for example, “only one active order per user”).

If access is exclusive, it can participate in a deadlock.

How to prevent resource-based deadlocks

- Never hold locks while making synchronous remote calls. Commit or release resources before calling another service.

- Define a global resource ordering. If multiple resources must be locked, always lock them in the same order across services.

- Reduce lock scope and duration. Short transactions. Minimal critical sections.

- Prefer async workflows for cross-service coordination. Events and message queues break circular waiting.

- Design idempotent operations. So retries do not extend lock lifetimes.

- Treat business invariants as resources. If an invariant is exclusive, explicitly design it.

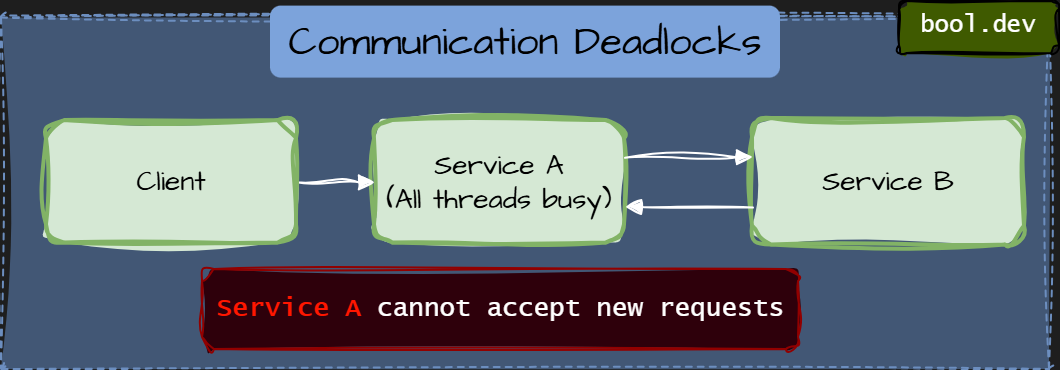

Communication Deadlocks

A communication deadlock occurs when services block each other through synchronous communication, even without explicit locks.

Each service waits for a response from another service, forming a cycle of blocking calls. No database locks. No distributed locks. Just waiting on the network.

This makes communication deadlocks especially tricky:

- Nothing looks “locked.”

- The thread pools are busy but not doing work

- Timeouts and retries often amplify the problem

What counts as a "blocked resource" in Communication Deadlocks

In communication deadlocks, the “resource” is implicit:

- threads

- request slots

- connection pools

- in-flight request capacity

Once a thread is blocked waiting for a response, it cannot process incoming requests that might unblock others.

How to prevent communication deadlocks

- Avoid synchronous call cycles. No service should synchronously depend on itself through other services.

- A service should never synchronously depend on itself, even indirectly.

- Prefer async communication for workflows. Queues and events break waiting chains.

- Separate inbound and outbound thread pools. So, blocked outbound calls do not block inbound requests.

- Set strict timeouts and fail fast. Waiting forever is worse than failing early.

- Apply bulkheads and concurrency limits. Limit the number of requests a service can block on downstream dependencies.

- Keep services behaviorally autonomous. A service should not require another service to complete its own request.

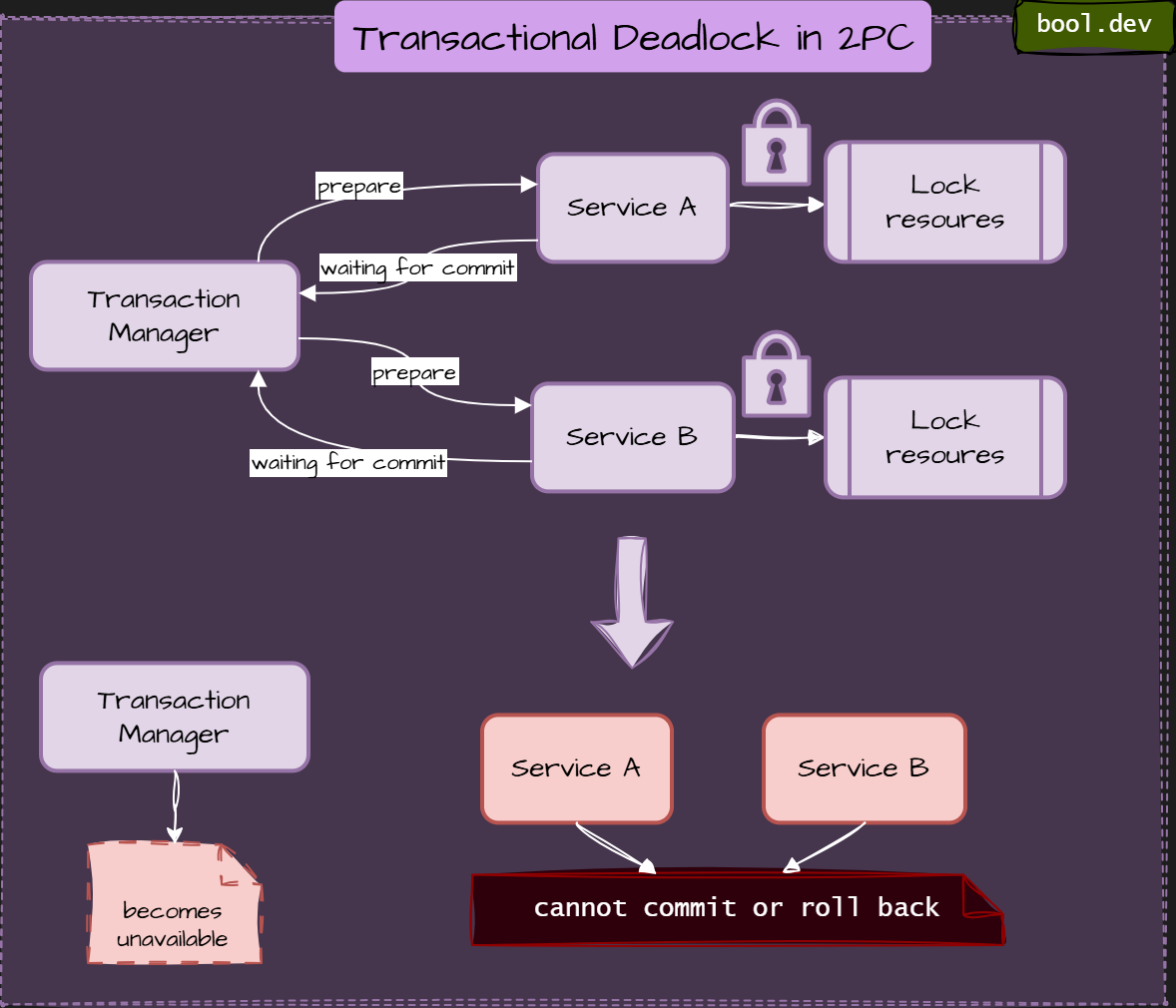

Transactional Deadlocks

Transactional deadlocks occur when distributed transactions or long-running workflows block each other, usually due to coordination protocols or incomplete rollback.

Unlike resource-based deadlocks, these do not always involve direct locks.

Instead, they are caused by transaction participants waiting for a global decision that never arrives.

This deadlock type is common in:

- two-phase commit (2PC)

- saga-based workflows with synchronous steps

- long-running business processes

What acts as a "blocked resource" in Transactional Deadlocks

In transactional deadlocks, the blocked resources are:

- transaction participants

- prepared but not committed data

- reserved business state (money, inventory, quotas)

- compensating actions waiting for execution

Once a participant enters a “prepared” or “pending” state, it may block others indefinitely.

Example deadlock in 2PC:

What happens step by step:

- Transaction Manager asks all participants to prepare

- Services A and B lock resources and respond “ready.”

- Transaction Manager becomes unavailable

- Participants cannot commit or roll back

- Locked state persists indefinitely

- No progress is possible without manual recovery.

How to prevent transactional deadlocks

- Avoid distributed transactions when possible. Prefer eventual consistency over global atomicity.

- Prefer Saga over 2PC. Sagas reduce deadlock risk, but only if steps and compensations are asynchronous and independent.

- Make compensation idempotent and independent. A rollback should not depend on another service being available or responsive.

- Set clear timeouts for prepared states. Prepared should not mean “forever”.

- Persist workflow state explicitly. So recovery can continue after failures.

- Design for partial failure first. Assume coordinators and participants will disappear.

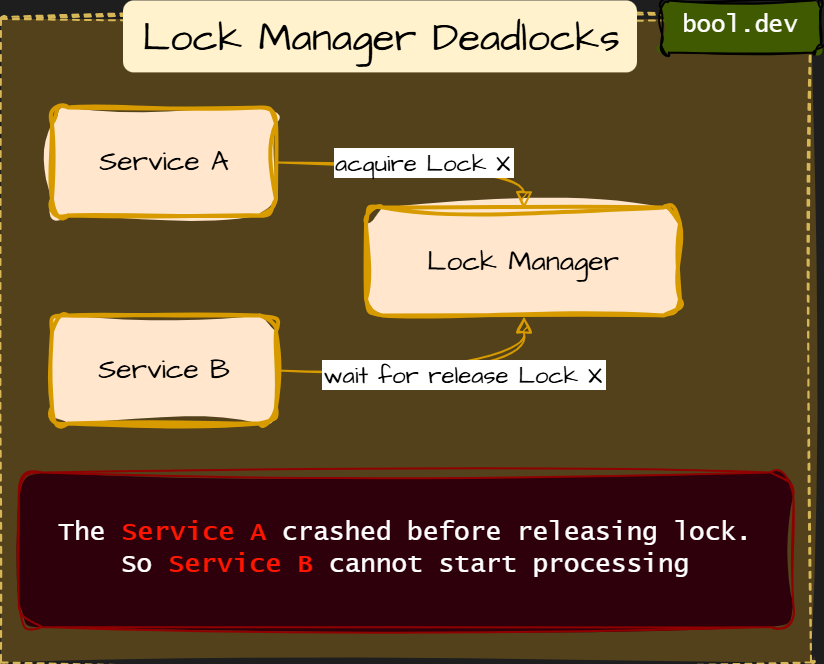

Lock Manager Deadlocks

Lock manager deadlocks occur when a centralized or semi-centralized lock service becomes the point where waiting chains form and never resolve.

Instead of services blocking each other directly, they all block through the lock manager.

This type of deadlock is subtle because:

- Services do not talk to each other

- The deadlock lives “inside” the coordination infrastructure

- failures look like infrastructure instability, not logic errors

Typical lock managers:

- Redis

- etcd

- ZooKeeper

- Consul

What acts as a "blocked resource" in Lock Manager

In this case, the resources are:

- distributed locks themselves

- lock leases

- sessions with the lock manager

- leadership or fencing tokens

If a lock is held but cannot be released safely, everyone else waits.

Example:

What happens step by step:

- Service A acquires a distributed lock

- Service A crashes or loses the network

- The lock is never released

- Service B waits indefinitely

If TTLs or fencing are misconfigured, this lock can live forever.

How to prevent lock manager deadlocks

- Prefer data-level guarantees over distributed locks

Databases are better lock managers than ad-hoc systems. - Always use lock TTLs. No lock should live longer than the business operation.

- Use fencing tokens. So stale lock holders cannot corrupt the state.

- Avoid acquiring multiple locks. If unavoidable, enforce strict lock ordering.

- Monitor lock duration and contention. Long-held locks are early warning signals.

- Treat the lock manager as critical infrastructure. Design for its partial failure explicitly.

Distributed Deadlock Comparison Table

| Deadlock Type | Primary "Resource" Being Held | Common Trigger | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource-Based | Database rows, Redis keys, or API locks | Services holding a lock while waiting for another service | Global resource ordering and avoiding locks during remote calls |

| Communication | Threads, connection pools, and request slots | Circular synchronous call chains (A > B > A) | Use async communication, strict timeouts, and bulkhead patterns |

| Transactional | Prepared data or reserved business state | A Transaction Manager failing after participants "Prepare" | Prefer Sagas over 2PC and ensure all rollback actions are idempotent |

| Lock Manager | Distributed leases or fencing tokens | A service crashing or losing network without releasing a lock | Mandatory Lock TTLs (Time-To-Live) and fencing tokens |

Key Takeaways

- Most distributed systems do not implement accurate deadlock detection and instead rely on timeouts, retries, and recovery.

- Never Hold a Lock During a Network Call: This is the most common cause of resource-based deadlocks. Commit your local transaction before contacting another service.

- Use "Timeouts" Everywhere: A communication deadlock happens because something is willing to wait forever. Set strict timeouts for every outbound request.

- Design for "Preemption" with TTLs: Since you cannot "steal" a resource back in a distributed system, you must ensure resources expire automatically via Time-To-Live (TTL) settings.

- Monitor workflow progress, not just service health. Deadlocks often happen in healthy systems.