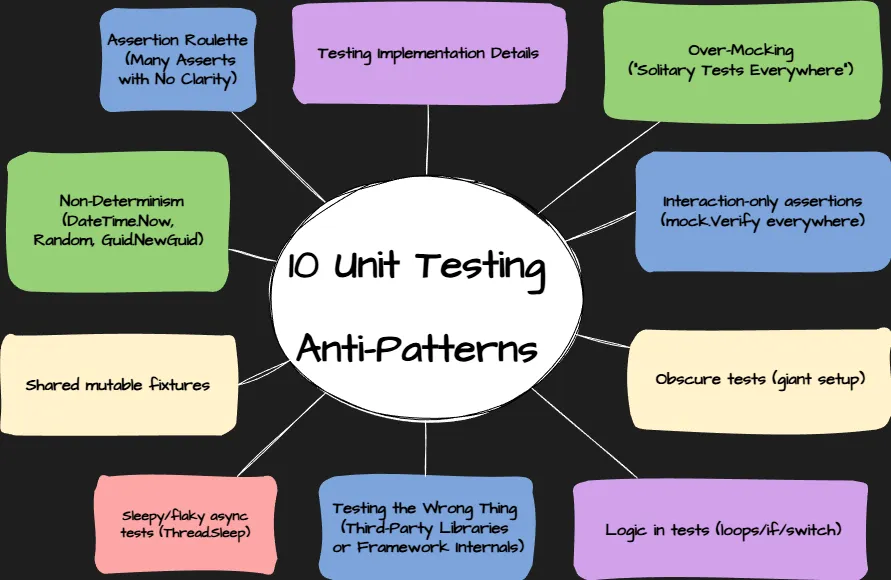

Top 10 Unit Testing Anti-Patterns in .NET and How to Avoid Them

A healthy unit test suite is supposed to be your safety net: fast feedback, reliable results, and the confidence to refactor. But many .NET codebases drift into a place where tests become fragile, slow, and tightly coupled to implementation details.

This article collects the most common unit test anti-patterns (“test smells”) you’ll see in .NET projects and shows practical fixes.

FIrstly lets discuss the project structure and what to cover and what not to cover by unit tests:

Anti-Pattern 1: Testing Implementation Details

Smell

- Reflection to call private methods

InternalsVisibleToadded purely for tests- Asserting “private helper X was called.”

Example:

// ❌ Bad: testing a private method via reflection (brittle, implementation-coupled)

[Fact]

public void CalculateTax_ReturnsExpected()

{

var order = new Order(/* ... */);

var method = typeof(Order).GetMethod("CalculateTax",

BindingFlags.Instance | BindingFlags.NonPublic);

var tax = (decimal)method!.Invoke(order, null)!;

Assert.Equal(2.50m, tax);

}Fix

Test via public API

If private logic is complex, extract it into a separate class with a clear responsibility and test that class through its public surface.

// ✅ Good: test behavior via public API

[Fact]

public void Finalize_AddsTaxToTotal()

{

var order = new Order(subtotal: 50m, taxRate: 0.05m);

order.Finalize();

Assert.Equal(52.50m, order.Total);

}

When private logic is genuinely complex

Extract it into a separate class with a public contract:

public sealed class TaxCalculator

{

public decimal Calculate(decimal subtotal, decimal rate) => subtotal * rate;

}

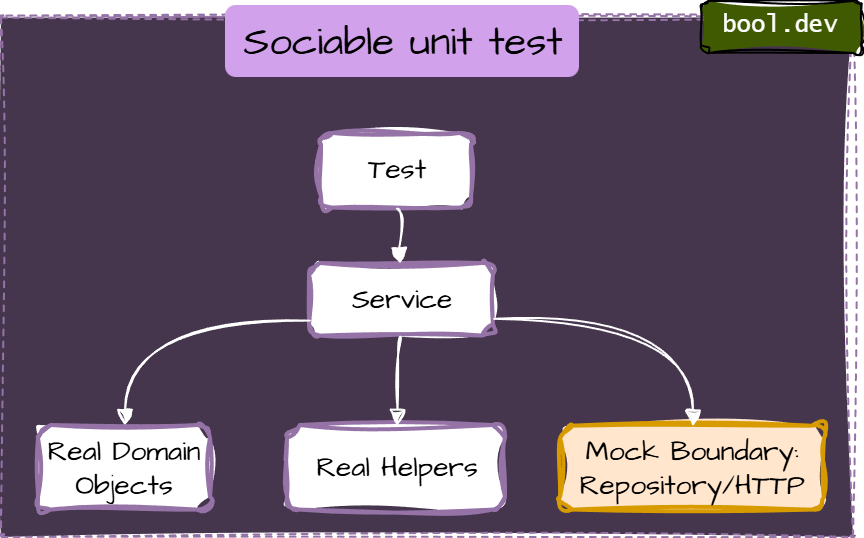

Anti-Pattern 2: Over-Mocking (“Solitary Tests Everywhere”)

Smell

A test mocks every dependency—even simple domain objects and internal helpers—so the test setup mirrors the internal code structure. It's also calls solitary unit test

Example (bad): mocking internal helpers

// ❌ Bad: mocking mapper + validator (internal structure leaks into test)

[Fact]

public async Task CreateUser_CallsMapper_ThenSaves()

{

var mapper = new Mock<IUserMapper>();

var validator = new Mock<IUserValidator>();

var repo = new Mock<IUserRepository>();

mapper.Setup(m => m.Map(It.IsAny<CreateUserRequest>()))

.Returns(new User("alice"));

validator.Setup(v => v.Validate(It.IsAny<User>())).Returns(true);

var sut = new UserService(mapper.Object, validator.Object, repo.Object);

await sut.CreateUser(new CreateUserRequest("alice"));

mapper.Verify(m => m.Map(It.IsAny<CreateUserRequest>()), Times.Once);

validator.Verify(v => v.Validate(It.IsAny<User>()), Times.Once);

repo.Verify(r => r.Save(It.IsAny<User>()), Times.Once);

}

Fix: Prefer “Sociable” Unit Tests

- Use real implementations for internal collaborators (domain models, value objects, simple calculators). Mock only true boundaries:

- database repositories (if you’re unit-testing application logic)

- external HTTP APIs

- message buses

- filesystem

- clock/time and randomness

// ✅ Better: real mapper/validator (internal), mock only repository (boundary)

[Fact]

public async Task CreateUser_PersistsValidUser()

{

var repo = new Mock<IUserRepository>();

var sut = new UserService(

mapper: new UserMapper(),

validator: new UserValidator(),

repo: repo.Object);

await sut.CreateUser(new CreateUserRequest("alice"));

repo.Verify(r => r.Save(It.Is<User>(u => u.Name == "alice")), Times.Once);

}

Even better: if your service returns a result, assert that too:

[Fact]

public async Task CreateUser_ReturnsCreatedUserId()

{

var repo = new InMemoryUserRepository(); // fake boundary, still deterministic

var sut = new UserService(new UserMapper(), new UserValidator(), repo);

var id = await sut.CreateUser(new CreateUserRequest("alice"));

Assert.True(repo.Exists(id));

}

Anti-Pattern 3: Interaction-only assertions (mock.Verify everywhere)

Smell

Interaction assertions are sometimes useful at boundaries (“did we call the HTTP client?”), but they become brittle when used to verify internal steps.

Example: verifying “how”

// ❌ Brittle: couples test to internal persistence strategy

repo.Verify(r => r.Save(order), Times.Once);

repo.Verify(r => r.Flush(), Times.Once);Fix: assert outcome/state

If you’re unit testing domain/application logic, assert state:

[Fact]

public void Finalize_SetsStatusToFinalized()

{

var order = new Order(subtotal: 100m, taxRate: 0.1m);

order.Finalize();

Assert.Equal(OrderStatus.Finalized, order.Status);

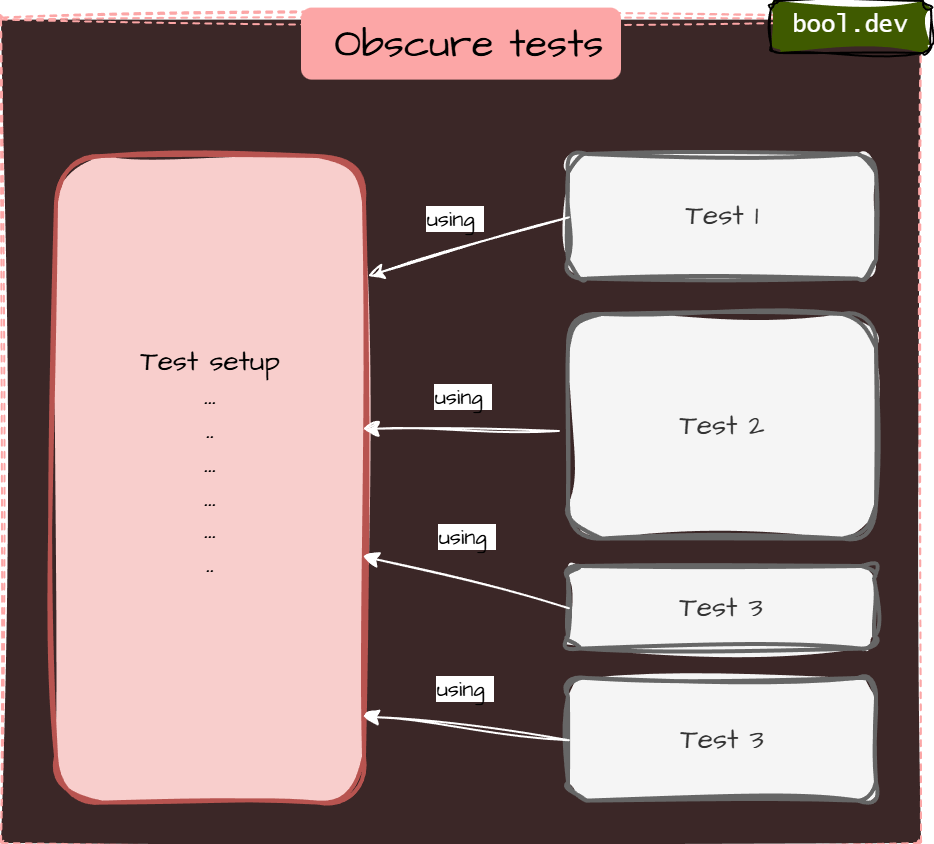

}Anti-Pattern 4: Obscure tests (giant setup)

Smell

- 100+ lines of setup

- The important inputs are buried

- copying setup across tests

Fix: AAA + Test Data Builder

public sealed class OrderBuilder

{

private decimal _subtotal = 100m;

private decimal _taxRate = 0.1m;

public OrderBuilder WithSubtotal(decimal value) { _subtotal = value; return this; }

public OrderBuilder WithTaxRate(decimal value) { _taxRate = value; return this; }

public Order Build() => new Order(_subtotal, _taxRate);

}

Test becomes readable:

[Fact]

public void Finalize_ComputesTotal()

{

var order = new OrderBuilder()

.WithSubtotal(50m)

.WithTaxRate(0.05m)

.Build();

order.Finalize();

Assert.Equal(52.50m, order.Total);

}

Anti-Pattern 5: Logic in tests (loops/if/switch)

Smell

Tests contain branching logic. Now you’ve written code inside your test that also needs testing

Example (bad)

[Fact]

public void DiscountRules_Work()

{

foreach (var subtotal in new[] { 99m, 100m, 150m })

{

var order = new Order(subtotal, taxRate: 0m);

order.ApplyDiscounts();

if (subtotal >= 100m)

Assert.True(order.HasDiscount);

else

Assert.False(order.HasDiscount);

}

}

Fix: parameterized tests

- Keep tests linear and explicit.

- Use parameterized tests instead of loops:

- xUnit:

[Theory]+[InlineData] - NUnit:

[TestCase]

- xUnit:

Example (xUnit)

[Theory]

[InlineData( 99, false)]

[InlineData(100, true)]

[InlineData(150, true)]

public void ApplyDiscounts_SetsHasDiscount_WhenThresholdMet(decimal subtotal, bool expected)

{

var order = new Order(subtotal, taxRate: 0m);

order.ApplyDiscounts();

Assert.Equal(expected, order.HasDiscount);

}

Anti-Pattern 6: Sleepy/flaky async tests (Thread.Sleep)

Smell

Using fixed delays to “wait for work”.

Example (bad)

[Fact]

public async Task SendsEmailEventually()

{

var sut = new EmailDispatcher();

sut.Dispatch("a@b.com", "hi");

Thread.Sleep(1000); // ❌ flaky + slow

Assert.True(sut.WasSent);

}

Fix A: await the work (best)

If the API can expose a Task, do it:

[Fact]

public async Task SendsEmail()

{

var sut = new EmailDispatcher();

await sut.DispatchAsync("a@b.com", "hi");

Assert.True(sut.WasSent);

}

Fix B: poll with timeout (when you can’t await directly)

private static async Task Eventually(Func<bool> condition, TimeSpan timeout)

{

var start = DateTime.UtcNow;

while (DateTime.UtcNow - start < timeout)

{

if (condition()) return;

await Task.Delay(20);

}

throw new TimeoutException("Condition was not met within the timeout.");

}

[Fact]

public async Task SendsEmail_Eventually()

{

var sut = new EmailDispatcher();

sut.Dispatch("a@b.com", "hi");

await Eventually(() => sut.WasSent, TimeSpan.FromSeconds(2));

}

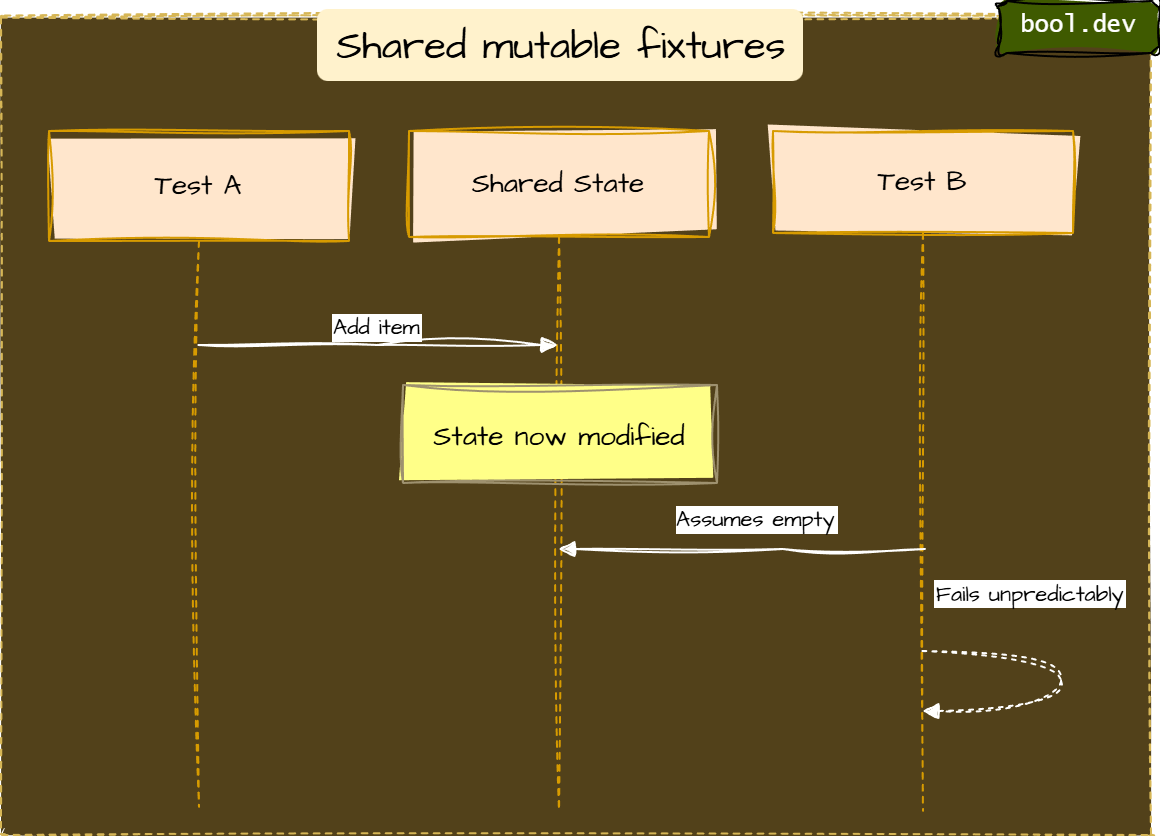

Anti-pattern 7: Shared mutable fixtures

Smell

Static/shared state reused across tests:

- shared in-memory list

- shared DB without reset

- singleton services holding state

Fix

- Make each test independent (fresh instances per test)

- Avoid static mutable state

- If a DB is unavoidable, isolate:

- create schema per test run/class

- Run tests in a transaction and roll back

- Use containerized ephemeral DB in CI (integration layer)

Anti-Pattern 8: Non-Determinism (DateTime.Now, Random, Guid.NewGuid)

Smell

Tests depend on:

- current time

- time zones/culture

- randomness

- machine-specific settings

Example

[Fact]

public void ExpiresInOneHour()

{

var token = Token.Issue(); // uses DateTime.Now internally

Assert.Equal(DateTime.Now.AddHours(1), token.ExpiresAt); // ❌ flaky

}Fix: inject a TimeProvider (.NET 8+)

public sealed class TokenService(TimeProvider timeProvider)

{

private readonly TimeProvider _timeProvider = timeProvider;

public Token Issue()

{

var now = _timeProvider.GetUtcNow();

return new Token(expiresAt: now.AddHours(1));

}

}

public sealed record Token(DateTimeOffset ExpiresAt);Register it:

builder.Services.AddSingleton(TimeProvider.System);

builder.Services.AddTransient<TokenService>();for testing use FakeTimeProvider from Microsoft.Extensions.TimeProvider.Testing nuget package

using Microsoft.Extensions.TimeProvider.Testing;

using Xunit;

public class TokenServiceTests

{

[Fact]

public void ExpiresInOneHour()

{

var fakeTime = new FakeTimeProvider();

fakeTime.SetUtcNow(new DateTimeOffset(2025, 01, 01, 10, 00, 00, TimeSpan.Zero));

var sut = new TokenService(fakeTime);

var token = sut.Issue();

Assert.Equal(fakeTime.GetUtcNow().AddHours(1), token.ExpiresAt);

}

}

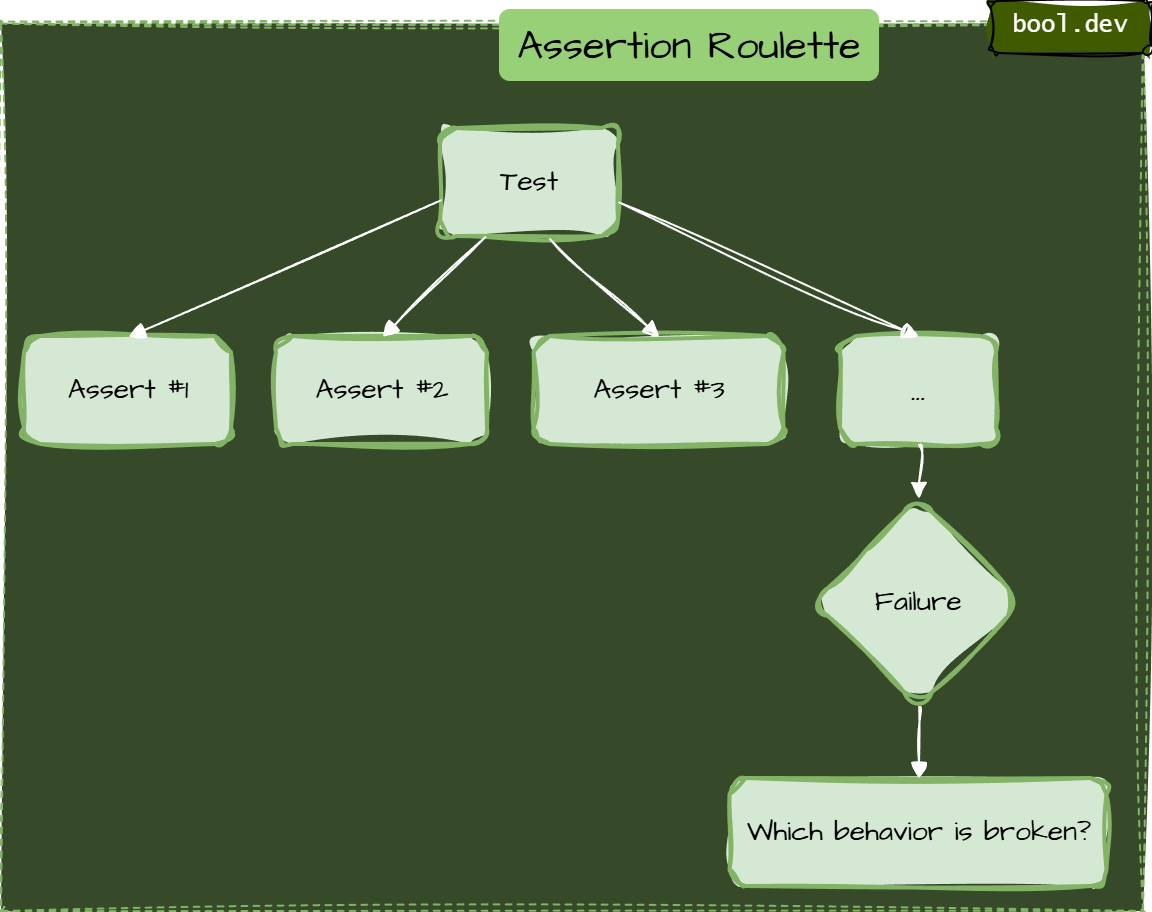

Anti-Pattern 9: Assertion Roulette (Many Asserts with No Clarity)

Smell

A single test contains a long list of assertions, and when it fails, you don’t immediately know which behavior broke.

Typical causes:

- testing multiple behaviors at once

- using plain

Assert.True(...)repeatedly without clear intent - validating an entire object graph in one go

Bad: “kitchen sink” test

[Fact]

public void CreateUser_SetsEverythingCorrectly()

{

var user = User.Create("alice@example.com", "Alice");

user.Email.Should().Be("alice@example.com");

user.Name.Should().Be("Alice");

user.IsActive.Should().BeTrue();

user.CreatedAt.Should().BeAfter(DateTime.UtcNow.AddMinutes(-1));

user.Roles.Should().Contain("User");

user.AuditTrail.Should().NotBeNull();

user.AuditTrail!.Events.Should().NotBeEmpty();

user.Profile.Should().NotBeNull();

user.Profile!.DisplayName.Should().Be("Alice");

user.Profile!.Locale.Should().Be("en-US");

}

Even if this test is “correct”, it’s hard to diagnose and tends to become brittle as the model evolves.

Fix A: Split by behavior

Write one test per meaningful rule:

[Fact]

public void CreateUser_SetsEmailAndName()

{

var user = User.Create("alice@example.com", "Alice");

user.Email.Should().Be("alice@example.com");

user.Name.Should().Be("Alice");

}

[Fact]

public void CreateUser_IsActiveByDefault()

{

var user = User.Create("alice@example.com", "Alice");

user.IsActive.Should().BeTrue();

}

[Fact]

public void CreateUser_AddsDefaultUserRole()

{

var user = User.Create("alice@example.com", "Alice");

user.Roles.Should().Contain("User");

}Fix B: Use “assertion scopes” to improve failure signal

If you do need multiple asserts (e.g., for a single cohesive behavior), make failures easier to read. FluentAssertions has AssertionScope:

using FluentAssertions.Execution;

[Fact]

public void CreateUser_InitializesDefaults()

{

var user = User.Create("alice@example.com", "Alice");

using (new AssertionScope())

{

user.IsActive.Should().BeTrue();

user.Roles.Should().Contain("User");

user.Profile.Should().NotBeNull();

}

}

Fix C: Prefer equivalence with explicit intent

Sometimes a concise “shape check” is best:

[Fact]

public void CreateUser_InitializesUser()

{

var user = User.Create("alice@example.com", "Alice");

user.Should().BeEquivalentTo(new

{

Email = "alice@example.com",

Name = "Alice",

IsActive = true

}, options => options.ExcludingMissingMembers());

}

Anti-Pattern 10: Testing the Wrong Thing (Third-Party Libraries or Framework Internals)

Smell

You write unit tests that prove ASP.NET Core, EF Core, Newtonsoft/System.Text.Json, or AutoMapper behave as documented — without asserting your business rule or configuration intent.

This is common when tests are created to “increase coverage” rather than to protect behavior.

Bad example: testing JSON library behavior

[Fact]

public void SystemTextJson_SerializesCamelCase()

{

var json = JsonSerializer.Serialize(new { FirstName = "Alice" },

new JsonSerializerOptions { PropertyNamingPolicy = JsonNamingPolicy.CamelCase });

json.Should().Be("{\"firstName\":\"Alice\"}"); // ❌ testing the library

}

Better: test your contract or mapping configuration (integration-ish)

If your API contract requires camelCase, test your endpoint (or your serialization settings) in a minimal integration test.

Example: ASP.NET Core minimal integration test using WebApplicationFactory (conceptual):

[Fact]

public async Task GetUser_ReturnsCamelCasedJsonContract()

{

// Arrange: boot app with real JSON settings

using var app = new WebApplicationFactory<Program>();

var client = app.CreateClient();

// Act

var response = await client.GetStringAsync("/users/1");

// Assert: verify contract you own (keys you promise)

response.Should().Contain("\"firstName\"");

}

This doesn’t “test System.Text.Json”; it tests your published API contract.

Bad: testing EF Core internal behavior as a unit test

[Fact]

public void EfCore_TracksEntities()

{

using var db = new AppDbContext(/* ... */);

var user = new User("alice@example.com");

db.Users.Add(user);

db.ChangeTracker.Entries().Should().HaveCount(1); // ❌ EF internal behavior

}

Better: test your persistence mapping as an integration test

If you care that a User is persisted and can be loaded correctly, test that:

[Fact]

public async Task User_CanBePersistedAndLoaded()

{

// Use test database (or container) in integration tests

await using var db = TestDb.CreateContext();

var user = new User("alice@example.com");

db.Users.Add(user);

await db.SaveChangesAsync();

var loaded = await db.Users.SingleAsync(u => u.Email == "alice@example.com");

loaded.Email.Should().Be("alice@example.com");

}

This test protects your mapping + constraints + configuration, which is the part you actually own.

Summary

Unit tests are only valuable when they make change safer. If your suite punishes refactoring, it’s not a “strict” suite — it’s a tightly coupled one.

When you review your tests, aim for these outcomes:

- Test observable behavior through the public API.

- Mock only true boundaries (DB/HTTP/MQ/filesystem/time), not internal helpers.

- Prefer state/outcome assertions over interaction choreography.

- Keep tests small, readable, and deterministic (no sleeps, no shared mutable state, no hidden randomness/time).

- Avoid assertion roulette by writing one test per rule (or using scopes intentionally).

- Don’t unit-test third-party libraries — use targeted integration tests to validate your wiring and contracts.

A practical litmus test to keep in mind:

If I can rewrite the internals completely and keep behavior the same, my tests should stay green.

That’s what a maintainable test suite looks like: it protects what matters, stays out of your way, and earns your trust every day.