Design Microservices: Using DDD Bounded Contexts

When people say “a microservice should do only one thing,” it sounds simple — but in reality, it’s the most challenging part. Without careful design, you end up with hidden coupling, shared models leaking everywhere, and services that break whenever another team touches a related area.

That’s where Domain‑Driven Design (DDD) helps. With its concept of Bounded Context (BC), you get a domain-driven way to draw boundaries. Each bounded context defines a consistent model, language, and rules. When you map those contexts to services, you get microservices that reflect the business — not just technology.

Why are Bounded Contexts Important

- A bounded context ensures that a model and language stay consistent. Within its borders, every term and rule has one meaning. Outside — meanings may shift. That avoids the confusion when different parts of the system use the same term in various ways.

- If you try to force a single model across everything, you risk a “big ball of mud.” One model that attempts to cover multiple business areas becomes complex, brittle, and difficult to evolve.

- Bounded Contexts allow teams to work independently. Each context can evolve its data, logic, and release cycle without affecting the rest of the system.

Microservices ≠ Bounded Context (always)

It’s often assumed that each bounded context maps to a single microservice. That’s a good starting point. But there are some concerns:

- Not all bounded contexts must map 1:1 to microservices. Sometimes a context is too large for a single service; you may split it. Other times, contexts may be small and multiple could be combined.

- A bounded context is a semantic boundary — not a guarantee of microservice shape or size by itself. Some argue that a bounded context by itself doesn’t define microservice boundaries.

That distinction matters: DDD gives you language and model boundaries. Deciding how that maps to deployable services depends on other concerns (non-functional requirements, scaling, team structure, etc.).

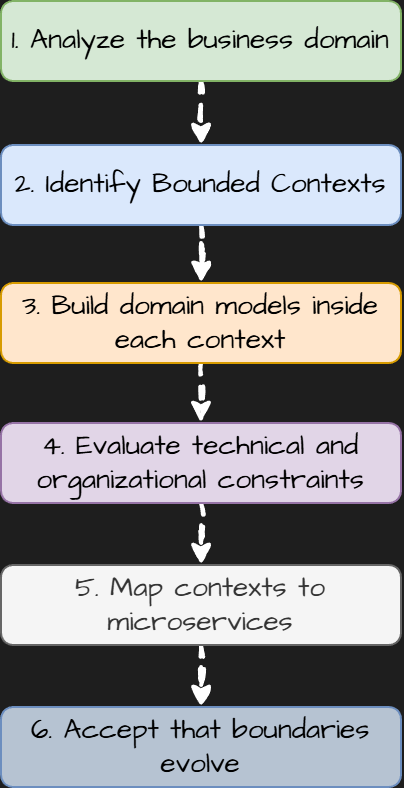

Step-by-step: from domain thinking to microservices

1. Analyze the business domain

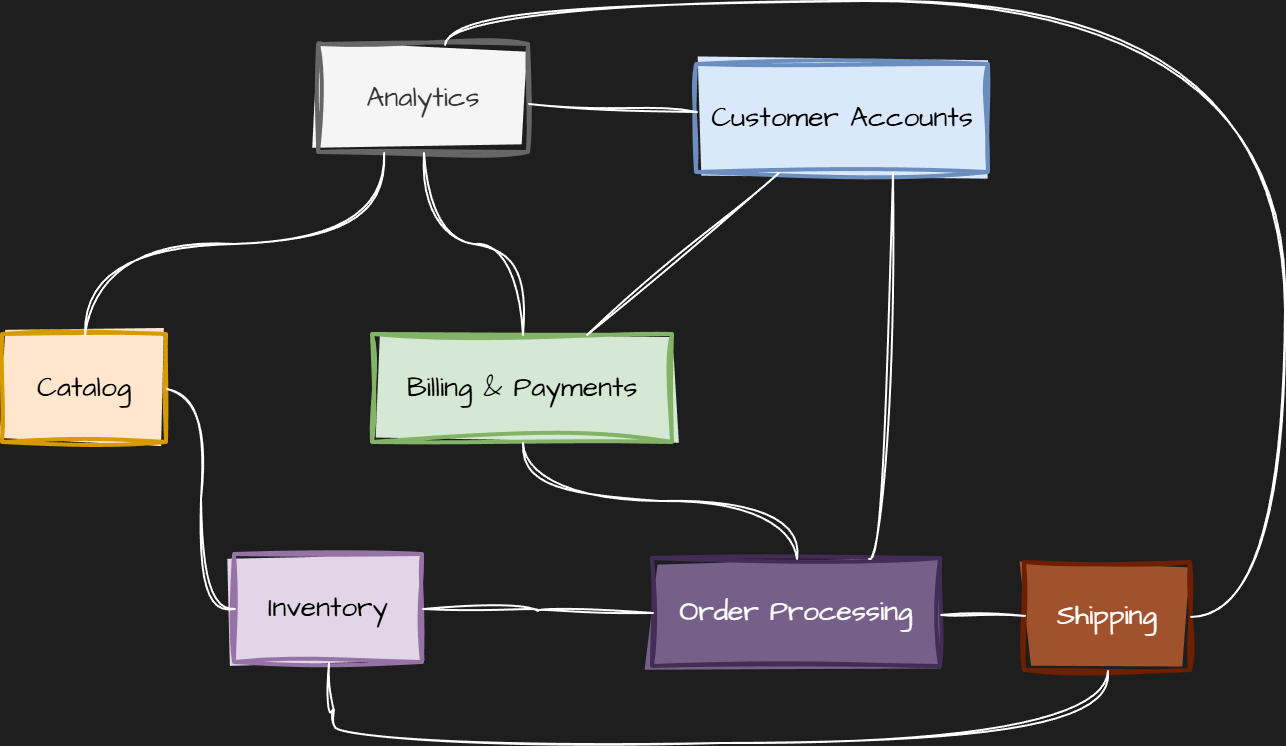

First, gather domain experts, stakeholders, and developers. Map out all business capabilities: catalog, inventory, orders, payments, shipping, customers, and analytics. Sketch how these parts connect, where data flows, and where dependencies or external systems (payment provider, delivery partner) might exist.

At this level, ignore databases, APIs, or technical layers. Focus solely on business behavior and processes. This helps you identify logical subdomains (catalog management, order processing, etc.), without deciding yet how they will be implemented.

2. Identify Bounded Contexts

Within subdomains, look for where language, meaning, and responsibilities diverge. A bounded context is where a domain model and its ubiquitous language stay valid. When meaning shifts, that suggests a new context.

Then sketch a context map: how contexts relate to one another, who talks to whom, and how. That becomes a blueprint for service boundaries.

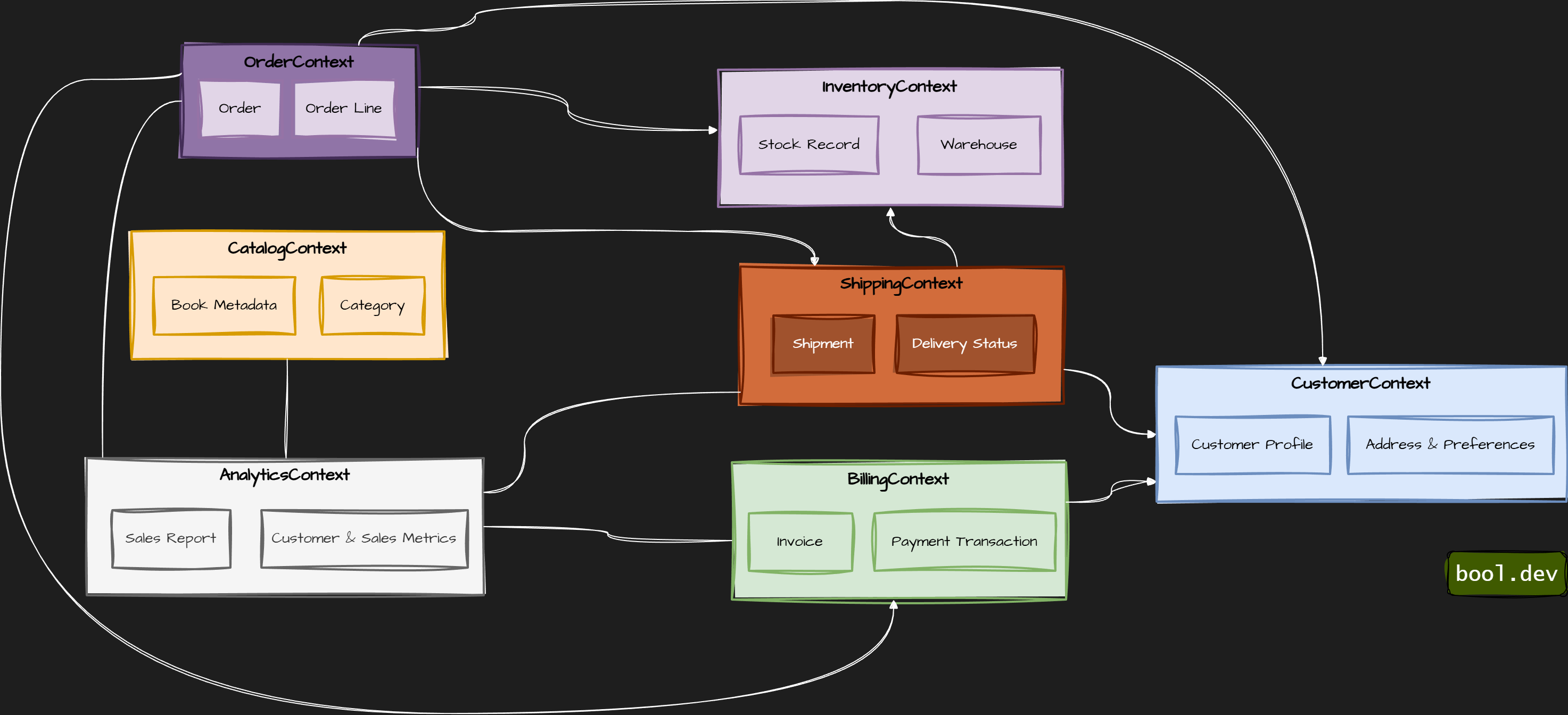

Example: book store

- CatalogContext — book metadata, categories, authors

- InventoryContext — stock levels, warehouses, reservations

- OrderContext — customer orders, order lifecycle, history

- CustomerContext — user profiles, addresses, preferences

- BillingContext — payments, invoices, billing history

- ShippingContext — shipment scheduling and status

- AnalyticsContext — sales stats, usage data, reporting

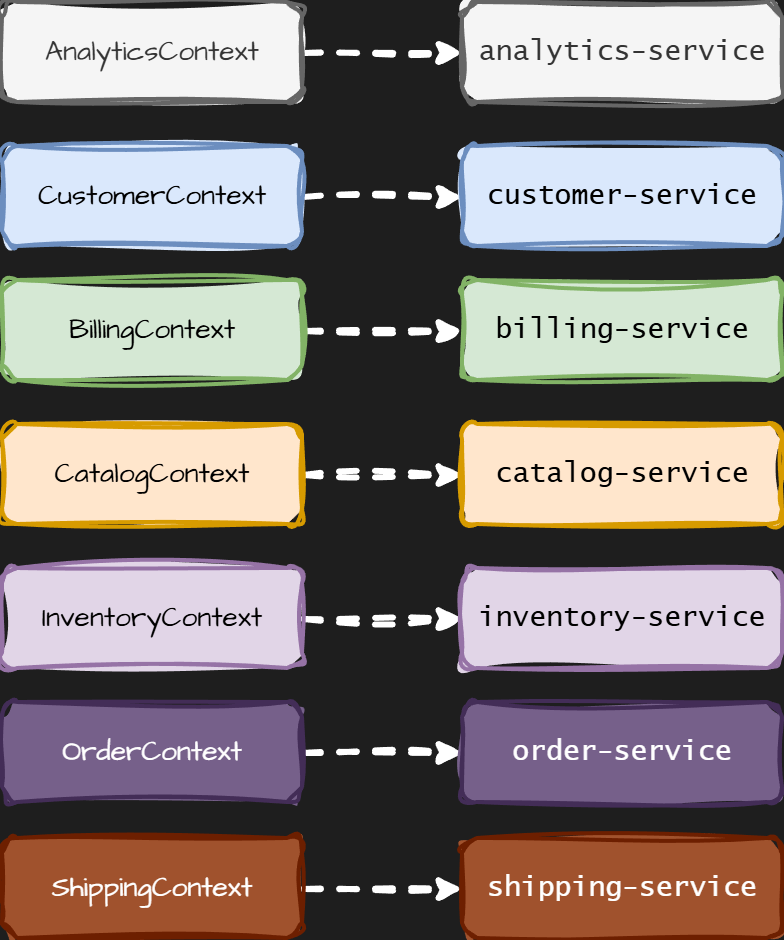

Bounded context for bookstore:

3. Build domain models inside each context

For each bounded context, define a domain model: entities, aggregates, value objects, and domain services — in line with DDD tactical patterns. Inside the context, the model represents what makes sense for that subdomain. External details (other contexts, infrastructure) stay out of it.

For example:

- In

CatalogContext, aBookentity might have atitle, anauthor, anISBN, and acategorylist. - In

InventoryContext, aStockRecordaggregate tracks warehouse, quantity, and reserved count. - In

OrderContext,Orderaggregate contains order lines, status, timestamps, references toCustomerandBillingdata (by id).

Each model stays cohesive and focused.

4. Evaluate technical and organizational constraints

Before mapping each bounded context to a microservice, consider non-functional requirements, such as scalability, data storage needs, deployment frequency, team responsibilities, and communication patterns.

These influence how you slice or group contexts into services. Sometimes a context is small and can be merged; sometimes it’s large and needs splitting.

5. Map contexts to microservices

Using the context map and technical/organizational constraints, decide how to implement services. Ideally, each microservice owns one or more bounded contexts (or parts of them), maintains its own data store, and exposes APIs or messages to communicate with other microservices. No shared database, no shared domain models across services.

For our bookstore, a possible mapping:

Each service works independently. When a customer places an order:

order-serviceasks inventory-service to reserve stockbilling-serviceprocesses paymentshipping-serviceschedules deliveryanalytics-servicelogs data

Communication occurs via API calls or domain events — no service directly accesses another’s database or domain model.

6. Accept that boundaries evolve

Business requirements change. Growth may bring new needs. As a result, bounded contexts and service boundaries may need to be adjusted. You might split a context/service, merge small ones, or refine models. DDD + microservices must stay flexible — design is iterative.

Summary

Using DDD and bounded contexts is a principled way to carve software into manageable, business-aligned pieces.

In our bookstore example:

- You analyze the domain and identify sub-domains.

- define bounded contexts for each coherent area;

- model each context independently;

- map contexts (carefully) to microservices, considering technical and organizational constraints;

- ensure each service owns its data, API, and model;

- allow the architecture to evolve as business changes.

This avoids shared-model chaos, hidden coupling, and brittle, tangled logic. Instead, you get clear meaning zones, team autonomy, and services that reflect business capabilities — not technical convenience.