Part 9: Microservices and Distributed Systems – C# / .NET Interview Questions and Answers

In this article, we explore microservices and distributed systems interview questions and answers, and what every .NET engineer should know, from service boundaries and BFF to sagas, events, service discovery, and communication patterns.

The Answers are split into sections: What 👼 Junior, 🎓 Middle, and 👑 Senior .NET engineers should know about a particular topic.

Also, please take a look at other articles in the series: C# / .NET Interview Questions and Answers

Service Architecture and Boundaries

❓ When does it make sense to isolate background processing into a separate microservice?

Isolating background processing makes sense when async work has different scaling, reliability, or lifecycle needs than the main request path. The goal is to protect user-facing flows and let background work evolve independently.

When isolation is a good idea

- Different scaling profile. Background jobs are CPU- or IO-intensive, or bursty. They should scale independently from the API that serves users.

- Long-running or unpredictable duration. Jobs run for seconds or minutes. Keeping them in the same service risks thread starvation, timeouts, and noisy neighbor effects.

- Failure isolation. Retries, poison messages, or backpressure in background work should not affect request latency or the API's availability.

- Different deployment cadence. Background logic changes more often or less often than the API. Separate services reduce coordination and risk.

- Different operational needs. Background workers need different limits, queues, schedules, or runtime settings than web APIs.

- Security and access boundaries. Workers may need broader access to internal systems that public-facing services should not expose.

When isolation is not needed

- Background work is trivial and short-lived.

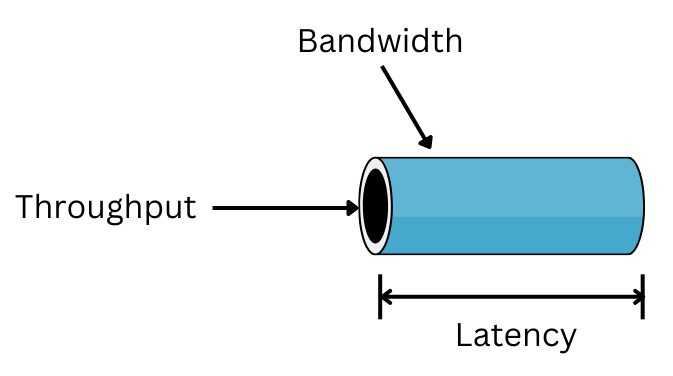

- Throughput is low and predictable.

- Failures do not impact user experience.

- The operational overhead of another service outweighs the benefits.

Common patterns

- Queue-based workers that pull jobs and process them asynchronously.

- Separate consumer services per workload type.

- Dedicated batch services with checkpointing and retries.

- Outbox in the API service and workers consuming events.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that unisolated background tasks can destabilize APIs; use basics like

BackgroundServiceor simple queues for separation. - 🎓 Middle: Apply queues/workers for differing workloads; use tools like Hangfire or MassTransit, monitoring dead-letters.

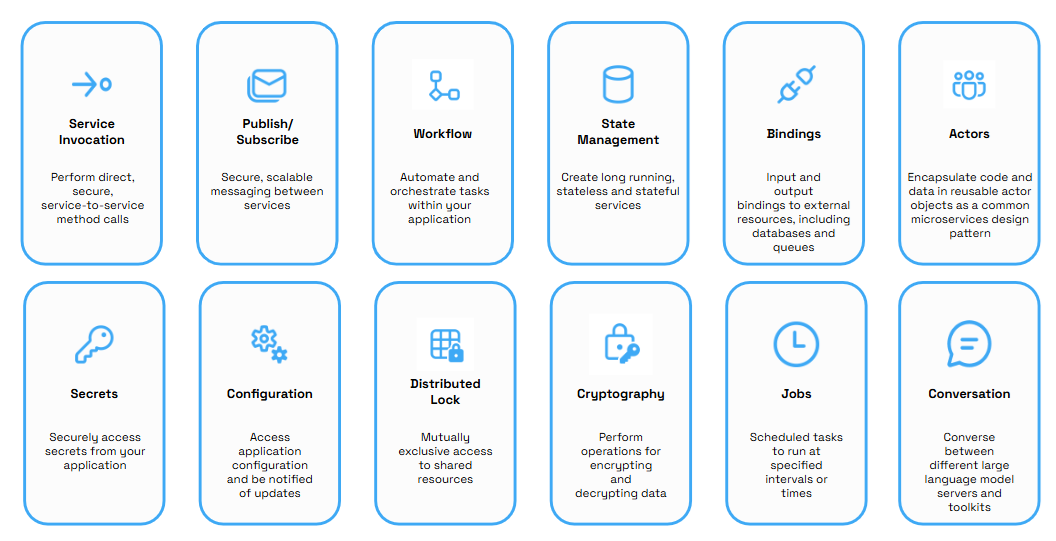

- 👑 Senior: Assess based on scaling/failures/ownership; design resilient systems with Polly, Dapr, ensuring security and consistency.

📚 Resources

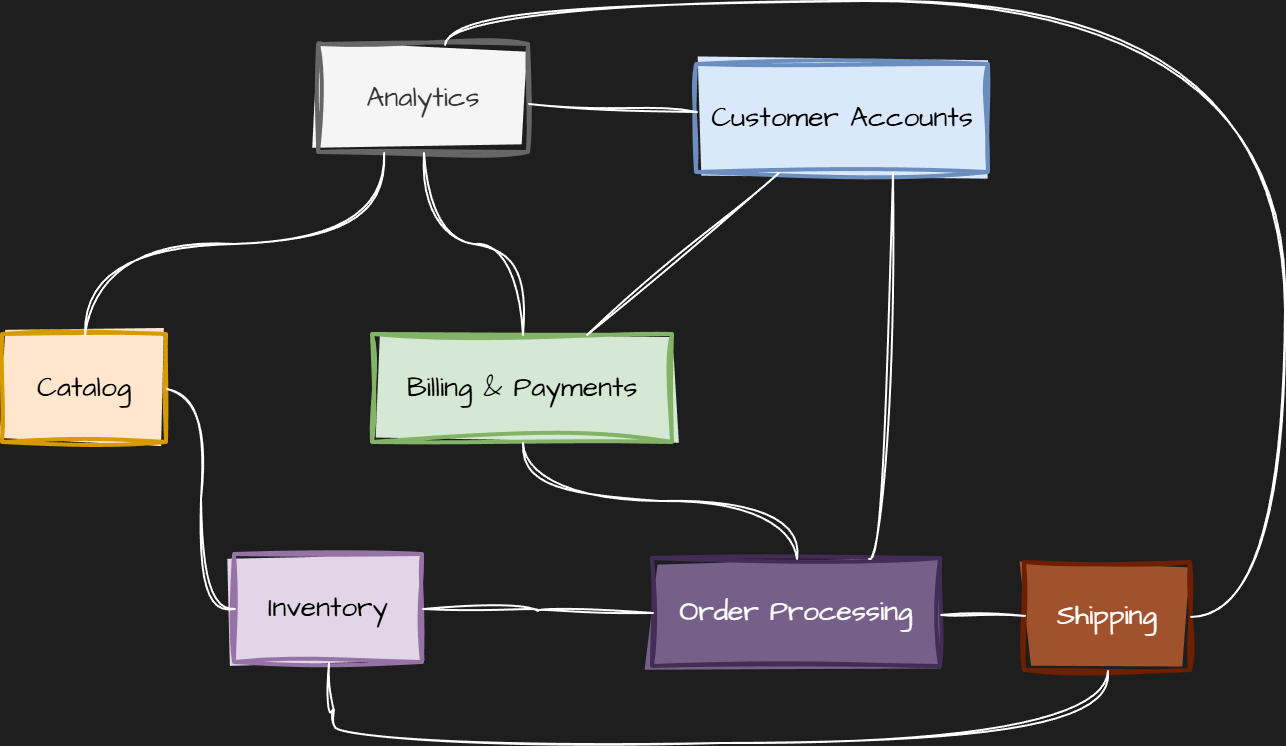

❓ How do you decide between a modular monolith and microservices?

A modular monolith is one deployable unit with well-defined internal boundaries. Microservices split the system into independently deployed services. The choice depends on domain maturity, team structure, and scaling needs — not trends.

When a modular monolith is a good choice

- The domain is still changing fast, and boundaries are unclear.

- The team is small, and coordination is easy.

- You want simple debugging, local development, and transactional consistency.

- You want to avoid the complexity of distributed systems (networking, retries, tracing, eventual consistency).

When microservices are a good choice

- Domain boundaries are stable, and teams can own services independently.

- Different parts of the system need different scaling profiles or SLAs.

- Release coupling becomes painful: one deploy blocks multiple teams.

- The system has real hotspots (search, billing, ML pipelines).

Bad reasons to choose microservices

“Everyone uses microservices now.”

“We want Kubernetes.”

“Monolith doesn’t scale” — without evidence.

Trying to fix the bad design by distributing it.

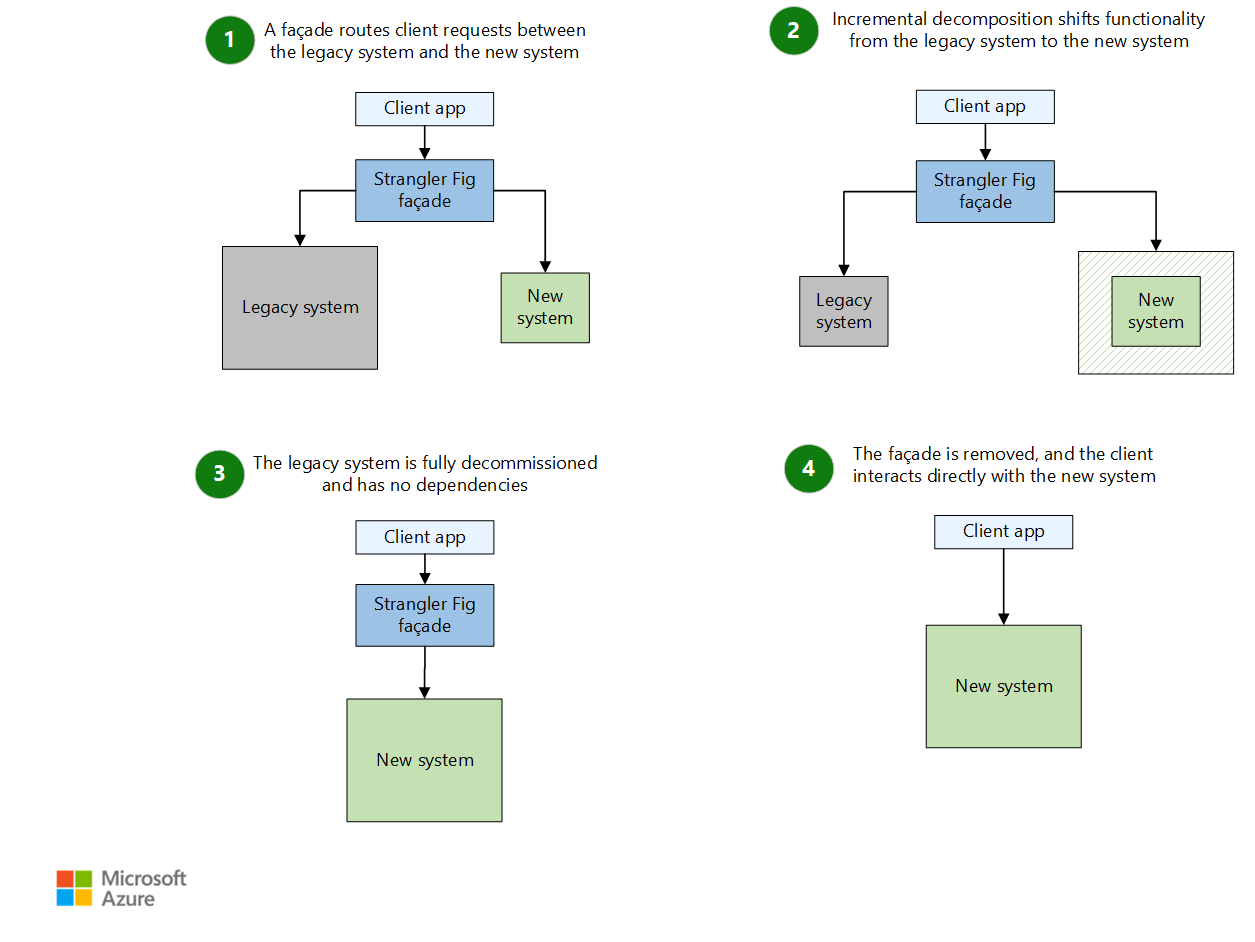

Extraction is usually incremental using the Strangler Fig pattern: route a small slice to a new service, keep the rest inside the monolith, grow slowly.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know monoliths are simpler for starters, using modules like separate projects in one solution; microservices split into apps, but add complexity.

- 🎓 Middle: Identify boundaries with DDD in .NET (e.g., bounded contexts); use microservices when scaling differs, via tools like ASP.NET Core APIs and Docker.

- 👑 Senior: Decide via domain analysis, team alignment (Conway's Law), and metrics; implement hybrids with .NET tools like Ocelot for gateways or Azure Service Fabric for orchestration.

📚 Resources:

❓ What is the Strangler Fig pattern, and how do you use it to migrate a legacy system?

The Strangler Fig pattern is a gradual migration approach where you build new functionality around a legacy system and slowly “strangle” the old parts until they disappear. Instead of a risky, significant rewrite, the old system and the new one run side by side. Traffic is routed to the new service only when its replacement is ready.

How the pattern works

- Identify a slice of functionality. A small, self-contained part of the legacy system (for example: authentication, invoice generation, reporting API).

- Add a facade/proxy to route requests.

- Implement a new service for that slice. Build the replacement in your new architecture (for example: .NET microservices).

- Switch traffic from legacy to new.

- Repeat slice by slice. Over time, the legacy system shrinks until nothing meaningful remains.

Why is this useful

- No “big bang” rewrite.

- Less risk — you replace functionality incrementally.

- You preserve business continuity.

- You can gradually test new services in production.

- Typical tools in .NET environments

- API Gateway (YARP, Ocelot)

- Reverse proxy routing rules

- Feature flags to move traffic gradually

- Message brokers to decouple old and new parts

Common mistakes

- Migrating too large a slice at once.

- Touching the database schema too early.

- Running both systems but failing to define a clear “source of truth”.

- Forgetting that routing rules are now part of your architecture.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Understand the idea of replacing old functionality step by step.

- 🎓 Middle: Know how to introduce a facade, isolate a functional slice, and migrate APIs safely.

- 👑 Senior: Strategize migrations with data sync, observability (e.g., App Insights), and de-risking via canary releases or flags.

📚 Resources: Strangler Pattern

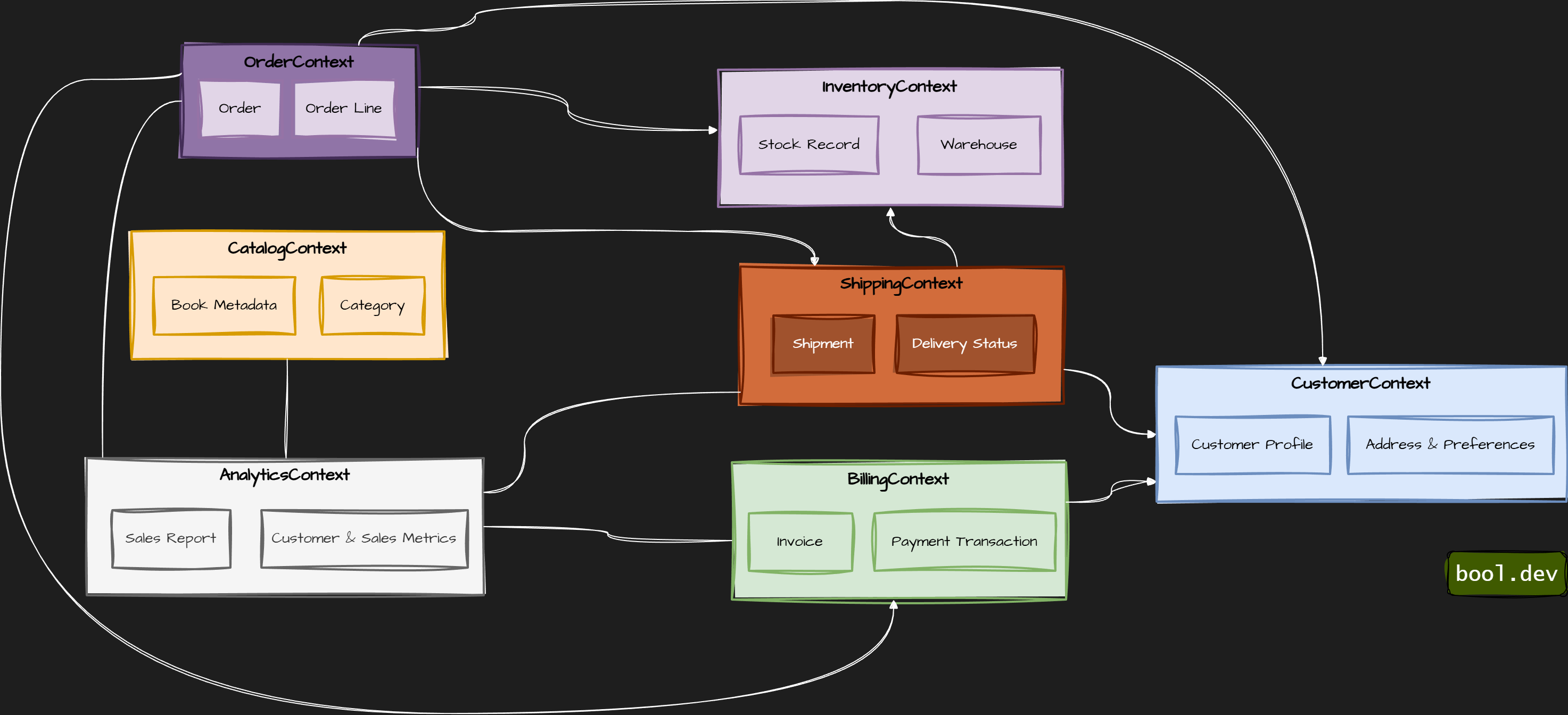

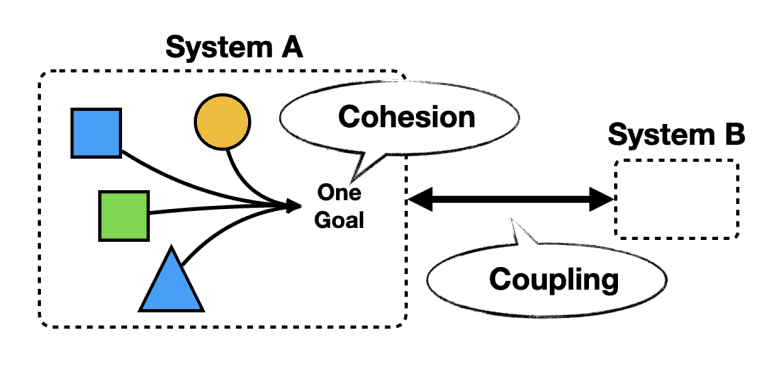

❓ How do you define service boundaries using DDD Bounded Contexts?

Bounded Contexts are a core idea in Domain-Driven Design. They describe clear, consistent “language zones” inside your domain. Each context has its own models, rules, and meaning. When you use them for microservices, each service becomes responsible for one context and nothing else.

The goal is simple: avoid a giant shared model and let each domain area evolve independently.

How to find Bounded Contexts

- Look at how language changes

In one part of the business, “Order” might mean a customer purchase. In another, “Order” could mean a warehouse picking task. Same word, different meaning — that is a natural boundary. - Map responsibilities. Group workflows that constantly change together. For example, pricing rules, inventory logic, and shipping logic change in blocks.

- Identify external dependencies when a part of the domain integrates with specific systems, as this usually indicates a separate context.

- Observe team structure. Teams are often aligned with business capabilities. Their ownership boundaries usually become good service boundaries.

- Keep models independent. No shared database schemas, no shared domain models. Each context can have its own representations, even if terms look similar.

Example: book store

- CatalogContext — book metadata, categories, authors

- InventoryContext — stock levels, warehouses, reservations

- OrderContext — customer orders, order lifecycle, history

- CustomerContext — user profiles, addresses, preferences

- BillingContext — payments, invoices, billing history

- ShippingContext — shipment scheduling and status

- AnalyticsContext — sales stats, usage data, reporting

Bounded context for bookstore:

Common mistakes

- Defining contexts as technical layers (API, DB, Frontend). These are not domain contexts.

- Splitting too finely, too early, ending with many tiny services.

- Sharing domain models across contexts destroys separation.

- Designing boundaries around REST endpoints instead of domain behavior.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Understand that the Bounded Contexts group domain logic belongs together and use separate models.

🎓 Middle: Know how to identify contexts based on language, workflows, and change patterns.

👑 Senior: Shape domain boundaries, enforce autonomy, and design contracts and events so contexts stay decoupled.

📚 Resources: Design Microservices: Using DDD Bounded Contexts

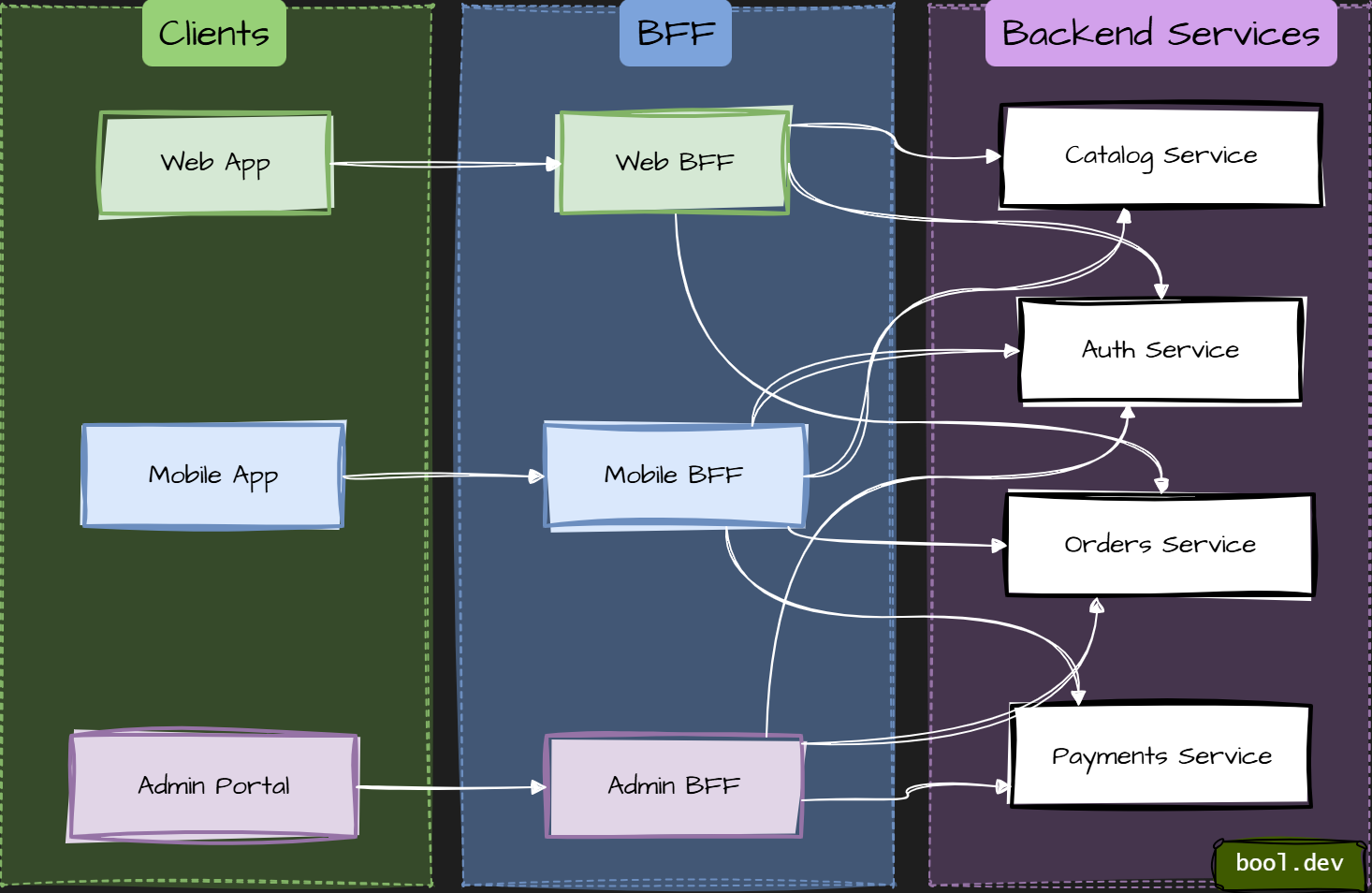

❓ What is Backends-for-Frontends (BFF), and where does it help?

Backends-for-Frontends (BFF) is an architectural pattern in which each frontend has its own dedicated backend. Instead of a single generic API serving all clients, you create a backend tailored to the needs of a specific UI, such as web, mobile, or admin.

The key idea: optimize APIs for user experience, not for reuse.

Why BFF exists

- Different frontends have different needs:

- Mobile apps want fewer calls and smaller payloads.

- Web apps may need richer data and faster iteration.

- Admin UIs often need bulk operations and detailed views.

- A single shared backend usually becomes bloated, full of conditionals, and hard to evolve. BFF avoids that.

What a BFF typically does

- Aggregates data from multiple services into one response.

- Shapes responses exactly for a specific UI.

- Handles auth, permissions, and user context for that frontend.

- Translates backend models into UI-friendly DTOs.

- Notably, a BFF contains no core business logic. It orchestrates, not decides.

Where BFF helps most

- Multiple frontends with very different requirements (Web, iOS, Android).

- Microservice architectures where UIs otherwise talk to many services.

- Teams that want the frontend and backend to evolve independently.

- High-latency environments where reducing round-trips matters.

- Typical .NET setup

- One ASP.NET Core app per frontend.

- Uses REST or gRPC to talk to internal services.

- Often sits behind an API Gateway or acts as one itself.

- Can be deployed and versioned together with the frontend.

Common mistakes

- Putting business rules into the BFF.

- Treating BFF as a generic shared API.

- Sharing BFFs between multiple frontends.

- Letting frontend teams bypass the BFF and call services directly.

What .NET engineers should know

👼 Junior: Know that BFF adapts backend APIs for a specific frontend.

🎓 Middle: Understand when one shared API becomes a bottleneck and how BFF reduces frontend complexity.

👑 Senior: Design BFFs as thin orchestration layers, align them with team ownership, and prevent business logic leakage.

📚 Resources: Backends for Frontends pattern

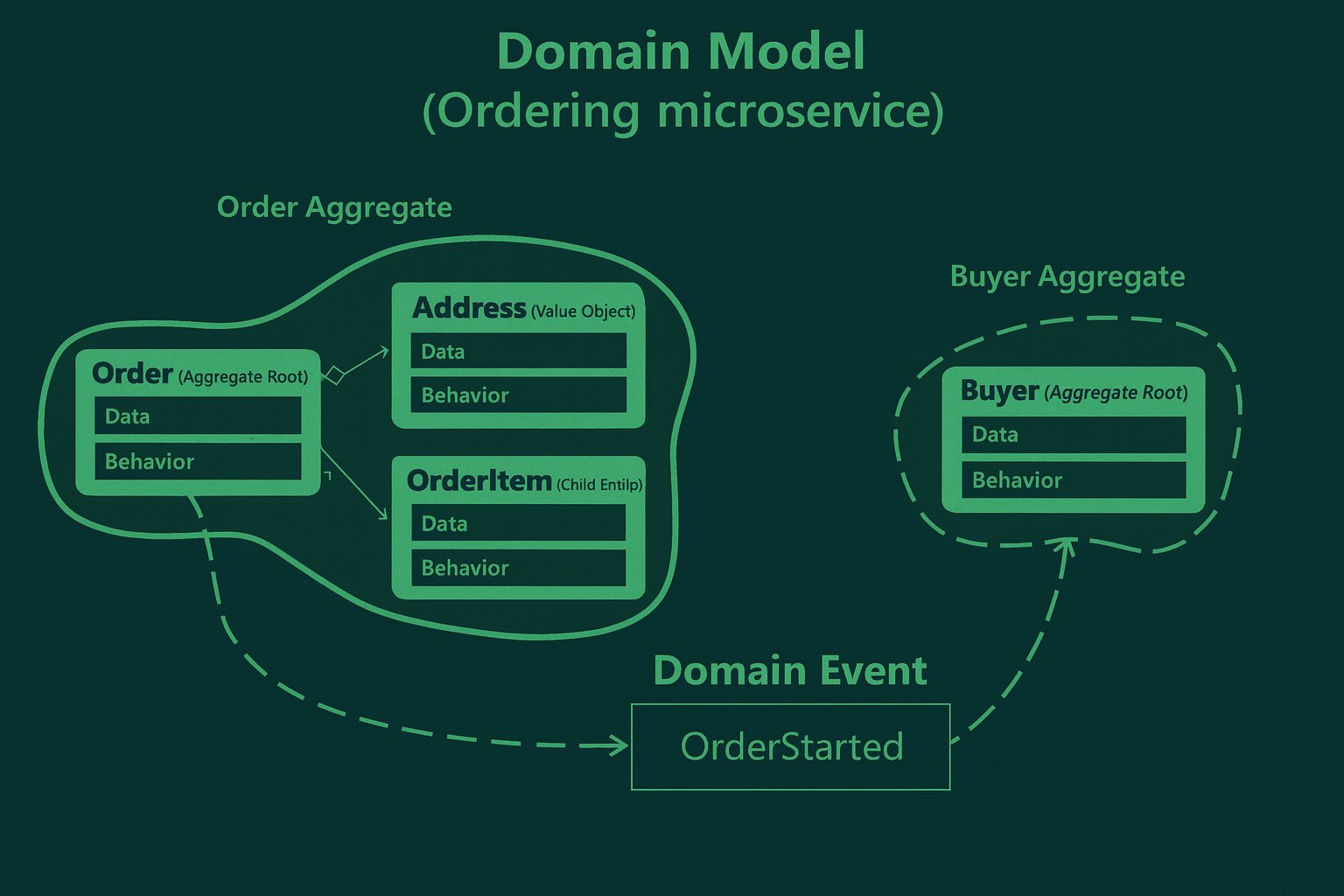

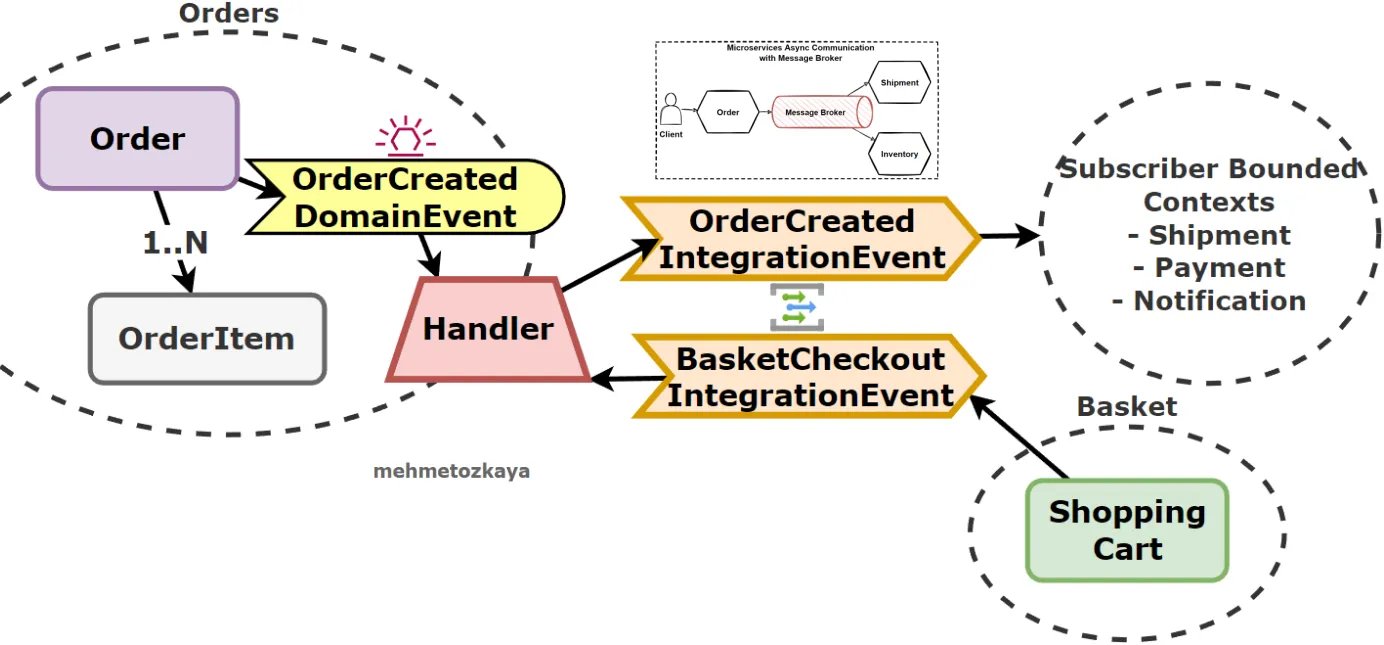

❓ What is the difference between a Domain Event and an Integration Event in a microservices architecture?

At the core, they are the same thing: “A representation of something that happened in the past. However, their purposes, use-cases, and implementation details are different:

Domain Events

- Domain Events are published and consumed within a single domain.

- You publish and subscribe to the event within the same application instance.

- They are strictly within the microservices/domain boundary.

- They typically indicate something that has happened within the aggregate.

- Domain events occur in-process and synchronously, sent via an in-memory message bus. Example: OrderStarted event

Integration Events

- They are used to communicate state changes or events between different bounded contexts or microservices.

- They are more about the overall system’s reaction to certain domain events.

- Integration Events should be sent asynchronously via a message broker using a queue.

- Other subsystems consume integration events.

- Example: After handling OrderPlacedEvent, an OrderPlacedIntegrationEvent might be published to a message broker like RabbitMQ, which other microservices could then consume.

What .NET engineers should know:

- 👼 Junior: Should understand that Domain Events describe internal events, and Integration Events are used for communication between services.

- 🎓 Middle: Expected to know how to publish and handle both kinds, and the need for eventual consistency in distributed systems.

- 👑 Senior: Should design systems using both patterns correctly, ensuring transactional safety with Domain Events and resilience/decoupling with Integration Events. Knows when to apply outbox patterns, message deduplication, and retry policies.

📚 Resources:

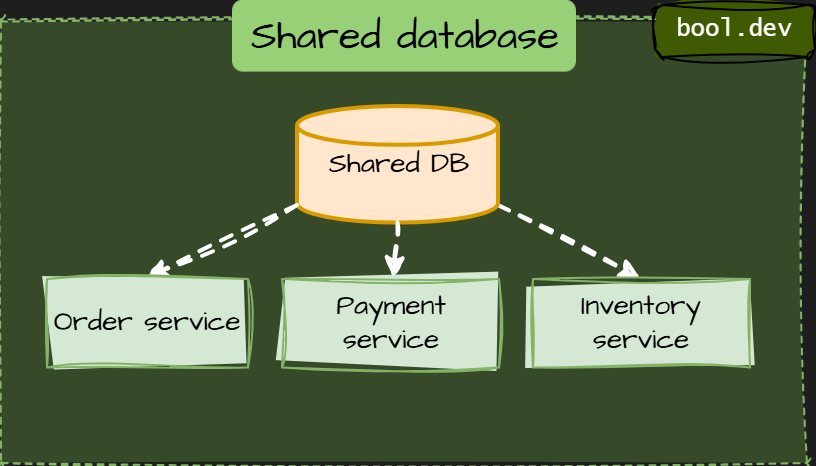

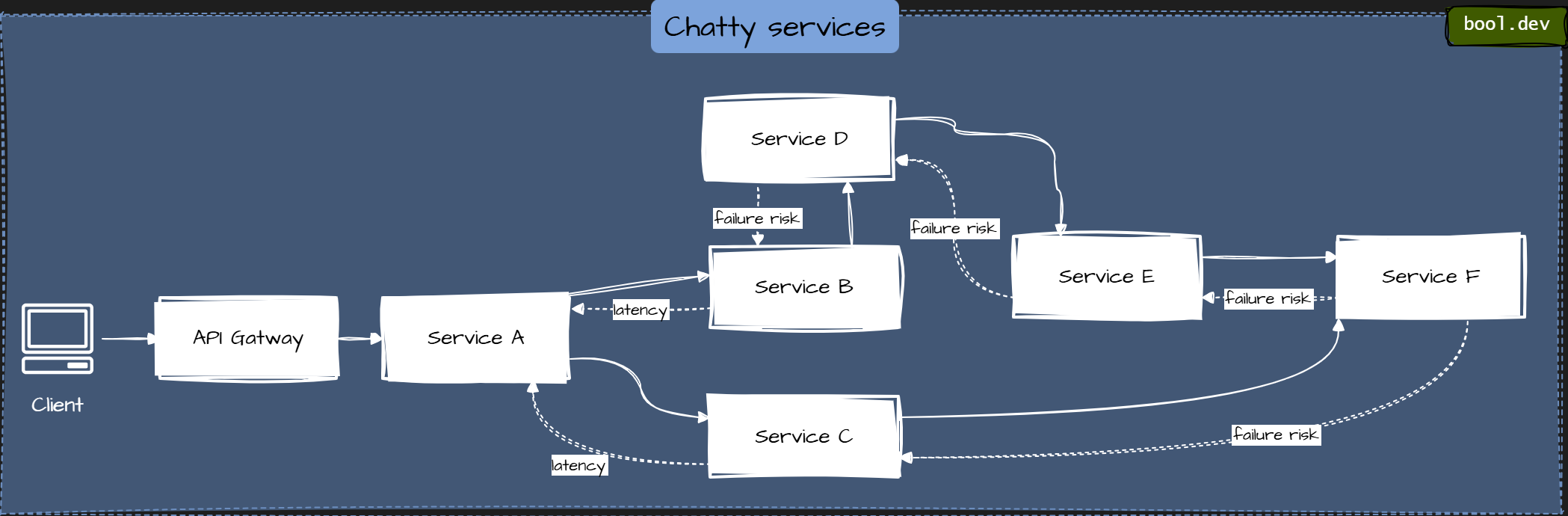

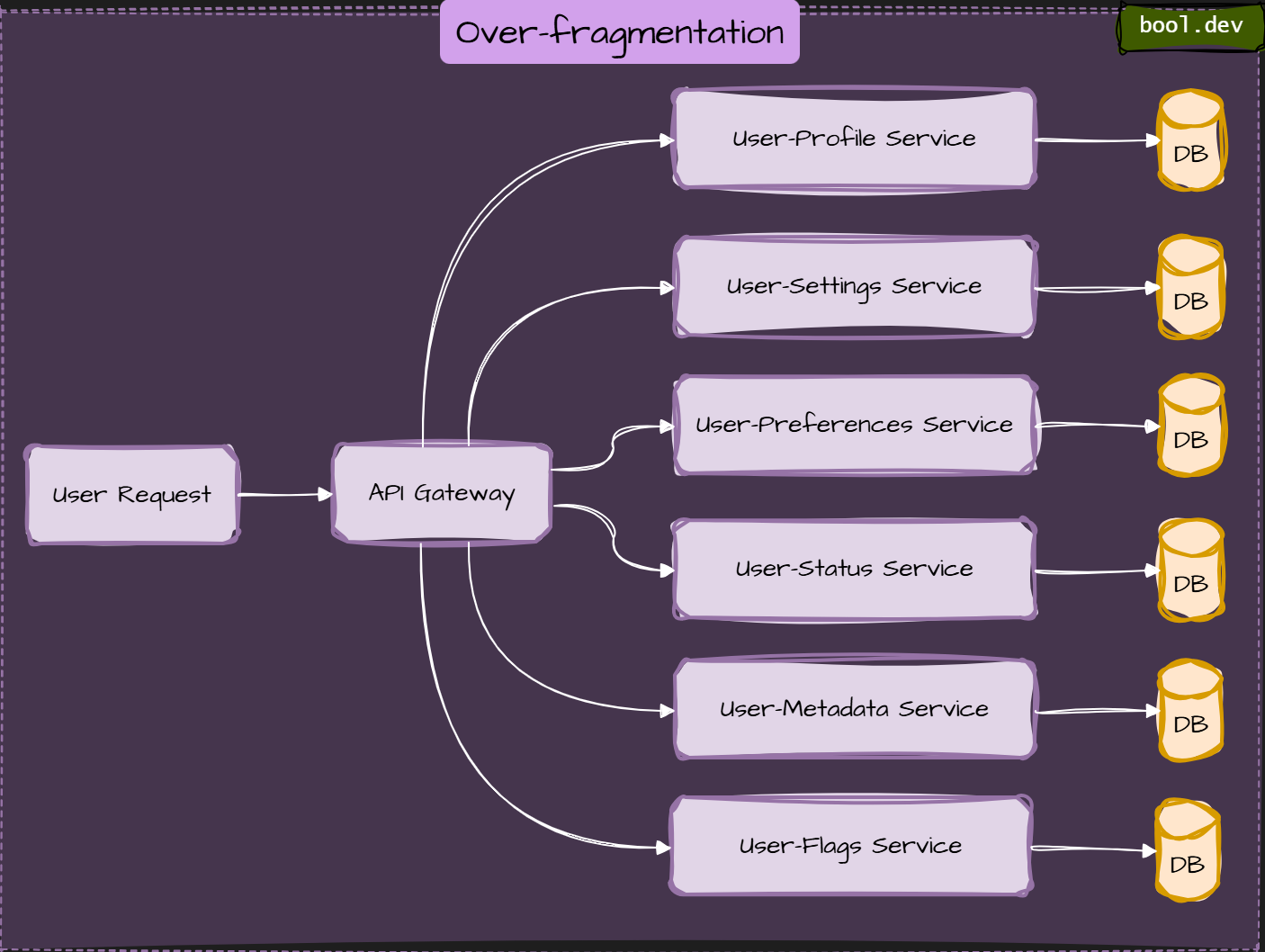

❓ What architectural smells appear when teams split a monolith into services?

When a monolith is split into services without clear domain boundaries, the same problems reappear. They move across the network. These problems are architectural smells. They signal that the system is distributed, but not truly decoupled.

Common architectural smells:

Shared database

Multiple services read and write the same database or schema. This creates hidden coupling and forces coordinated releases. It is the fastest way to rebuild a distributed monolith.

Chatty services

One user request triggers dozens of synchronous service calls. Latency grows, failures cascade, and simple features become fragile.

Business logic in the wrong place

Rules leak into API gateways, BFFs, or orchestration layers. Services become CRUD wrappers rather than owning behavior.

Tight deployment coupling

Services must be deployed together because changes in one break others. This usually means contracts are unstable or boundaries are wrong.

Distributed transactions everywhere

Two-phase commits or manual transaction coordination across services. This often hides poor service boundaries and leads to complex failure modes.

Over-fragmentation

Too many tiny services with no clear ownership. Operational cost grows faster than business value.

Anemic services

Services expose data but no behavior. All real logic lives in a central “core” service, which becomes the new monolith.

Why do these smells appear

- Splitting by technical layers instead of domain boundaries.

- Reusing old monolith models across services.

- Premature optimization or blind copying of “microservices at scale” examples.

- Fear of data duplication and eventual consistency.

How to spot problems early

- Every change requires touching multiple services.

- Teams hesitate to deploy independently.

- Performance issues appear after adding “just one more service.

- Debugging requires jumping through many logs without clear ownership.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Recognize shared databases and chatty calls as warning signs.

- 🎓 Middle: Identify coupling, misplaced logic, and unstable service contracts.

- 👑 Senior: Redesign boundaries, reduce synchronous dependencies, and align services with business capabilities.

❓ Compare Saga orchestration vs choreography for distributed transactions.

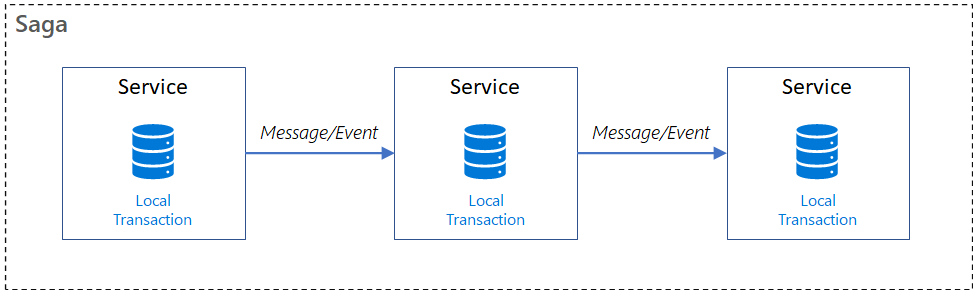

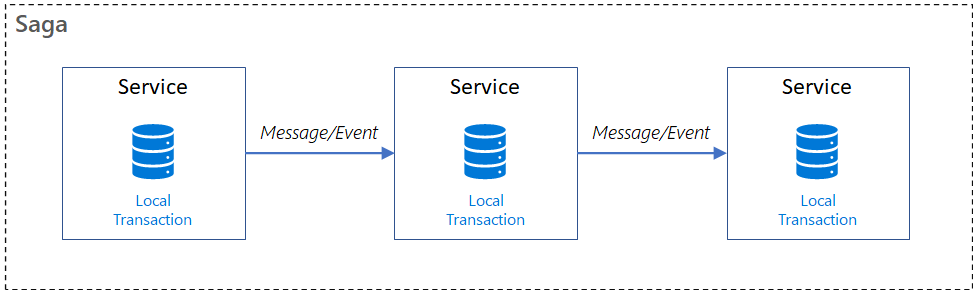

The Saga design pattern helps maintain data consistency in distributed systems by coordinating transactions across multiple services to ensure data integrity. A saga is a sequence of local transactions in which each service performs its operation and initiates the next step via events or messages. If a step in the sequence fails, the saga performs compensating transactions to undo the steps that have already completed. This approach helps maintain data consistency.

There are two main coordination styles: orchestration and choreography.

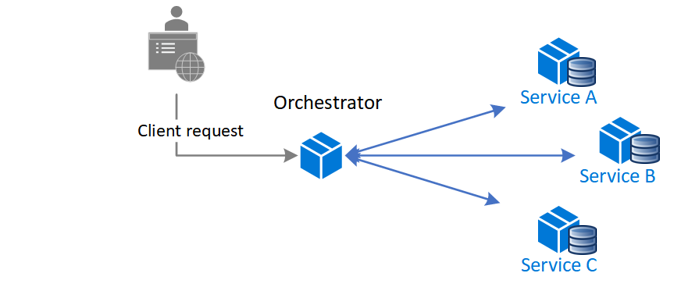

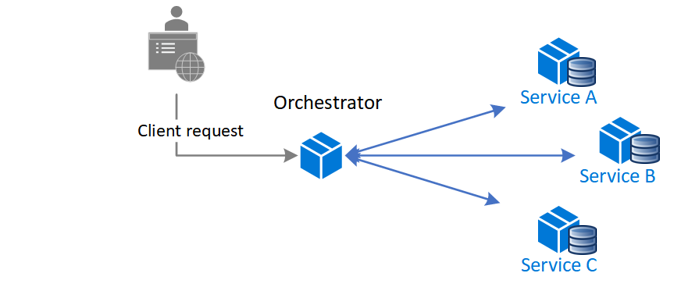

Orchestration:

A central orchestrator controls the flow.

How it works:

- The orchestrator instructs each service on what to do (e.g., “Create Order” and then “Reserve Inventory”).

- It waits for each step to succeed or fail.

- If something goes wrong, it triggers compensating actions in reverse.

Pros:

- Central logic is easy to follow and manage.

- Good for debugging and visibility

- Easier to enforce business rules

Cons:

- Tight coupling to the orchestrator

- Can become a “god service” if not modularized

Example:

// Pseudocode

await orchestrator.ExecuteSagaAsync(orderId);Choreography

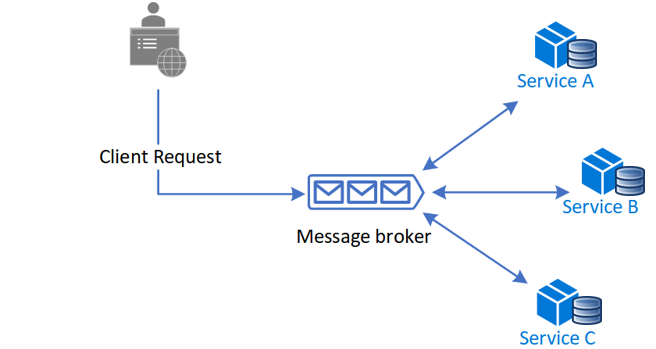

Each service responds to events and determines its next course of action.

How it works:

- There’s no central coordinator.

- Services publish and listen to events.

- Flow is driven by events like “OrderCreated → InventoryReserved → PaymentProcessed”.

Pros:

- Loosely coupled and scalable

- Services own their behavior

- Easy to evolve independently

Cons:

- Harder to trace the full flow

- Business logic is spread across services

- Error handling and compensation are more complex

Example:

// InventoryService listens for "OrderCreated"

public void OnOrderCreated(OrderCreatedEvent evt) =>

bus.Publish(new InventoryReservedEvent(evt.OrderId));Used in event-driven architectures with tools like Azure Service Bus, Kafka, or NServiceBus.

📚 Resources:

❓ What is Event-Carried State Transfer, and how does it reduce temporal coupling?

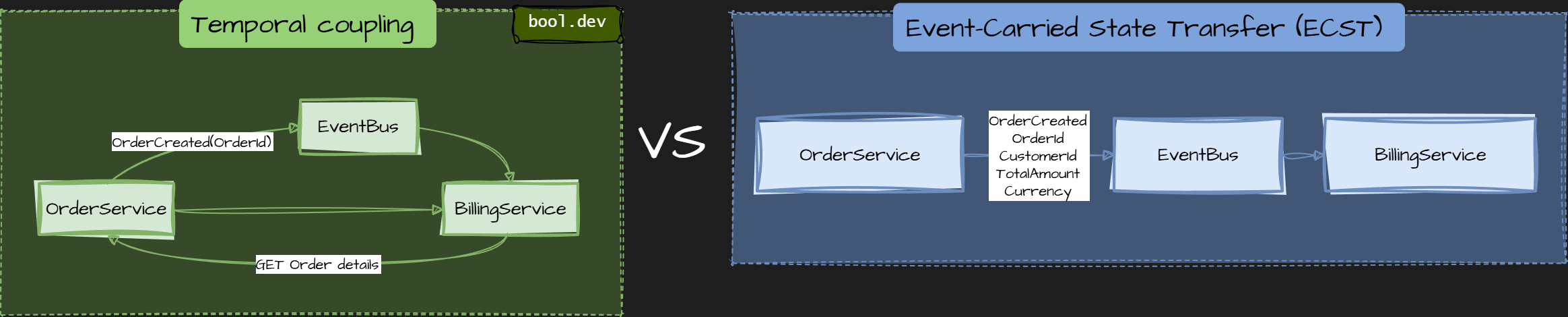

Temporal coupling occurs when Service B can process a message only if Service A is available at the same time. This usually appears when events contain only IDs and force consumers to make follow-up calls.

Event-Carried State Transfer (ECST) is a messaging pattern where an event contains all the data that consumers need, not just an identifier. Instead of publishing “something changed, go fetch the rest,” the service publishes the state itself.

The key idea: move data with the event so consumers do not depend on the producer being available later.

Trade-offs

- Events are larger.

- You may duplicate data across services.

- Schema evolution must be handled carefully with versioning.

Common mistakes

- Publishing only IDs and calling it event-driven.

- Publishing internal database models.

- Mutating past events or relying on consumers to “fix” missing data.

- Treating events as commands.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Understand that events can carry data, so consumers do not call back.

- 🎓 Middle: Know how ECST reduces runtime dependencies and improves resilience.

- 👑 Senior: Design event schemas, version them safely, and balance payload size with decoupling.

📚 Resources: What do you mean by “Event-Driven”?

Communication, Messaging, and Networking

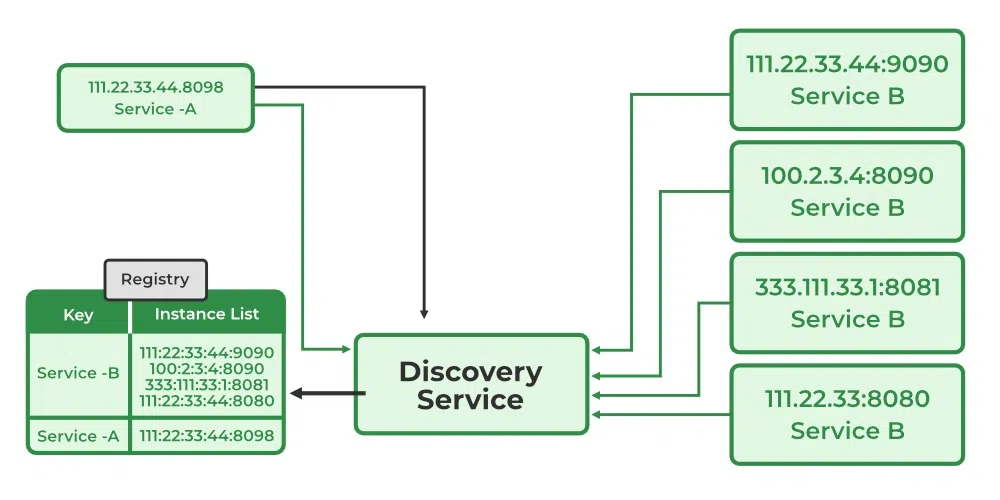

❓ What is service discovery, and how do client-side and server-side discovery differ?

Service discovery is the mechanism that enables services to find and communicate with each other without hardcoding network addresses. In dynamic environments like containers or cloud platforms, service instances come and go, so IPs and ports cannot be assumed to be static.

A Service Registry (like Consul, Eureka, or Kubernetes DNS) acts as a "phone book" that keeps track of the current network locations of all available service instances.

Service discovery answers a simple question:

“How does one service know where another service is right now?”

💻 Client-Side Discovery

In this pattern, the Client (the service making the call) is responsible for determining the network locations of available service instances and load-balancing requests.

- Register: Service instances register themselves with the Service Registry on startup.

- Lookup: The Client queries the Registry for a list of healthy instances for "Service B."

- Select: The Client uses a load-balancing algorithm (like Round Robin) to pick one instance.

- Call: The Client makes the request directly to that instance's IP.

Pros: Fewer network hops; the client can make intelligent, application-specific load-balancing decisions.

Cons: Couples the client to the Service Registry; you must implement the discovery logic in every programming language used in your system.

🌐 Server-Side Discovery

In this pattern, the client requests a Router or Load Balancer. The client doesn't even know the Service Registry exists.

- Register: Service instances register with the Service Registry.

- Call: The Client sends the request to a dedicated Load Balancer (e.g., NGINX, AWS ALB, or Kubernetes Service).

- Lookup: The Load Balancer queries the Registry (or uses its own internal list) to find available instances.

- Forward: The Load Balancer forwards the request to a healthy instance.

Pros: Simplifies client code, centralizes discovery logic, and works flawlessly across different programming languages.

Cons: Adds an extra network hop (the Load Balancer), which becomes a critical piece of infrastructure that must be highly available.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that services should not use hardcoded addresses.

- 🎓 Middle: Understand how clients resolve services dynamically and how load balancing works.

- 👑 Senior: Choose client-side or server-side discovery based on platform maturity and operational complexity.

📚 Resources:

❓ Why is DNS discovery not ideal in dynamic systems?

In dynamic systems like microservices, DNS isn't ideal because caching and TTLs can cause stale records and traffic to dead instances; there's no native health-aware load balancing (just round-robin); changes propagate slowly; and there's no app-level health checks, leading to black-holed requests.

Use alternatives like load balancers, Kubernetes Services, or service meshes for real-time scaling, health routing, and control.

Modern platforms need:

- Instant reaction to scaling events.

- Health-based routing.

- Fine-grained traffic control.

- Consistent behavior across languages.

This is why most systems use server-side discovery with load balancers, Kubernetes Services, or service meshes, often using DNS only as a stable entry point.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: DNS caching in .NET apps can send requests to failed instances; prefer simple registries for basics.

- 🎓 Middle: DNS lacks health awareness and fast reaction to scaling.

- 👑 Senior: Use DNS for stable endpoints, not for fast-changing service discovery.

📚 Resources:

❓ When is a service mesh worth the complexity?

A service mesh adds infrastructure for traffic, security, and observability in microservices. Use when: chatty calls cause latency/failures; need retries/circuit breakers without code; mTLS for secure comms; high tracing needs; mixed protocols (REST/gRPC).

In a microservices architecture, a service mesh is generally worth the complexity when the following conditions are met:

- When "Chatty Services" Become a Bottleneck: If a single user request triggers dozens of synchronous service calls, the resulting latency and fragile failure cascades make observability and traffic management in a service mesh necessary.

- Need for Advanced Reliability without Code Bloat: If you are manually implementing retries, circuit breakers, and timeouts across dozens of .NET services, a service mesh can offload this logic to the infrastructure layer, preventing "business logic in the wrong place".

- Complex Security Requirements (mTLS): In environments where every service-to-service call must be encrypted and authenticated, a service mesh automates mutual TLS (mTLS) without requiring each service team to manage certificates.

- High Observability Needs: When debugging requires "jumping through many logs without clear ownership," a service mesh provides standardized distributed tracing and metrics across all services by default.

- Hybrid Communication Styles: When a system heavily uses a mix of REST, gRPC, and Messaging, a service mesh helps manage the different performance profiles and discovery needs of these protocols in one place.

When to Avoid a Service Mesh

According to the article's logic on Over-fragmentation, a service mesh is likely not worth it if:

- The system is a Modular monolith or has very few services.

- The operational costs of the mesh grow faster than the business value it delivers.

- The team is small and can handle coordination through simpler tools like API Gateways (YARP/Ocelot).

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: A service mesh handles networking concerns outside application code.

- 🎓 Middle: Understand when retries, mTLS, and traffic control should move to infrastructure.

- 👑 Senior: Decide based on scale, security, and operational maturity, not trends.

📚 Resources:

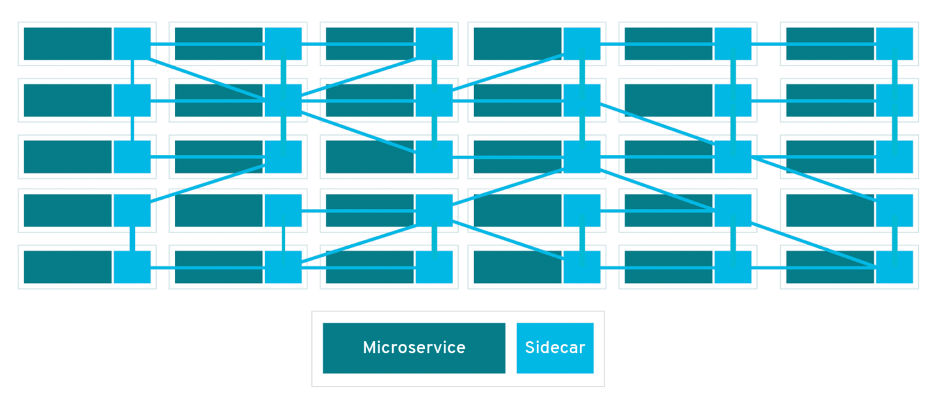

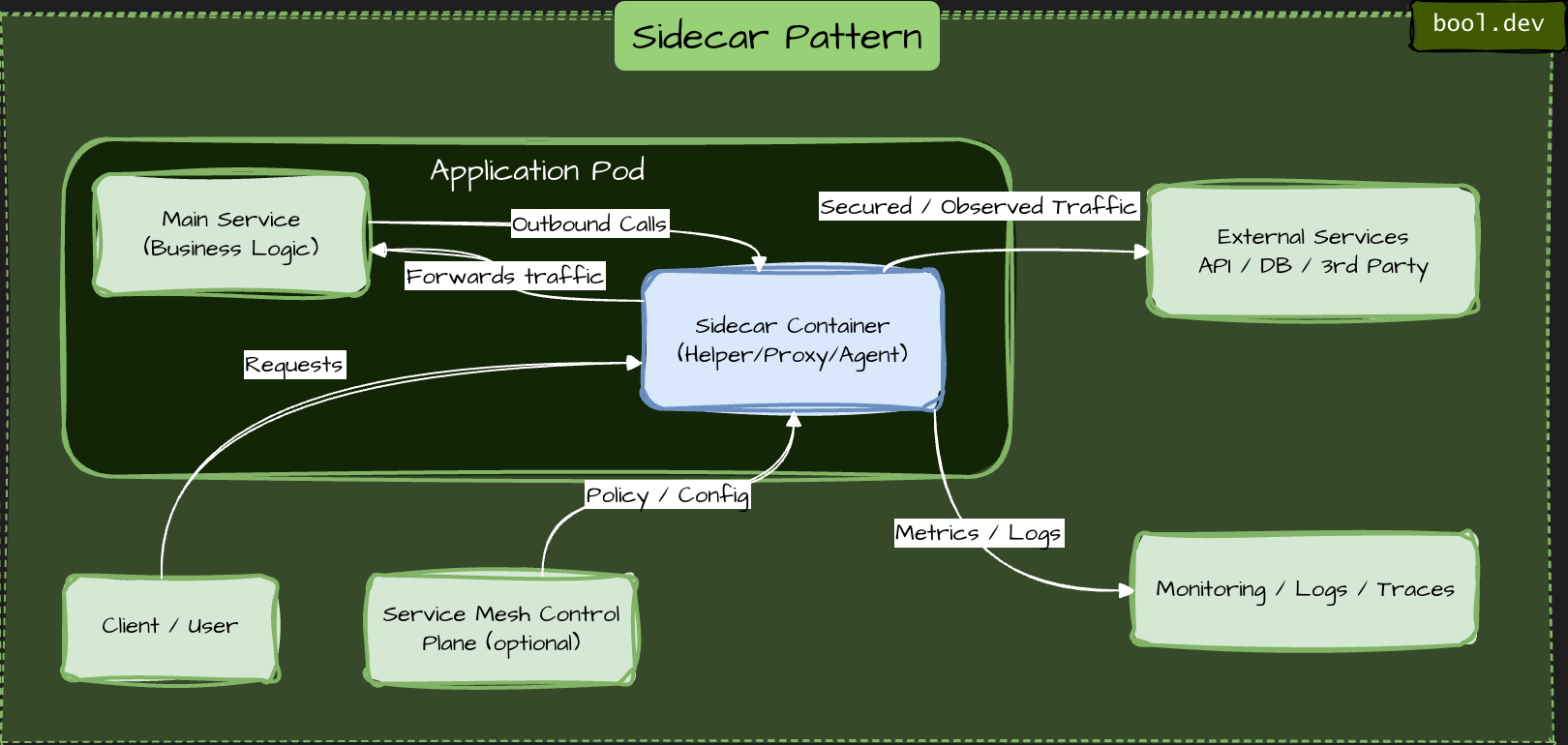

❓ What is a sidecar, and how is it used in distributed systems?

A sidecar is a design pattern in which a helper component runs alongside a service instance and extends its behavior without changing the service's code. The service and the sidecar are deployed, scaled, and restarted together, but they have separate responsibilities.

The idea is runtime separation of concerns.

What a sidecar does

A sidecar handles cross-cutting concerns that should not live in business code, such as:

- Service-to-service communication logic.

- Retries, timeouts, and circuit breaking.

- mTLS and certificate rotation.

- Metrics, logging, and distributed tracing.

- Configuration reloads or secrets management.

The application focuses only on business logic. The sidecar handles infrastructure concerns.

How it works in practice

- Each service instance runs next to its own sidecar.

- All inbound and outbound traffic goes through the sidecar.

- The sidecar intercepts, enriches, or controls traffic transparently.

- The service is unaware of most networking or security logic.

- In container platforms, services and sidecars typically run in the same pod or on the same host.

Where sidecars are commonly used

- Service meshes. Sidecars act as data-plane proxies that provide consistent networking across all services.

- Observability. Sidecars collect metrics, logs, and traces without modifying application code.

- Security. Sidecars enforce mTLS, authentication, and authorization policies centrally.

- Protocol adaptation. Sidecars can translate protocols or apply policies without changing the service itself.

Why sidecars are useful

- No duplication of infrastructure logic across services.

- Consistent behavior across languages and teams.

- Easier rollout of networking or security changes.

- Cleaner application code.

Trade-offs to be aware of

- Extra resource usage per service instance.

- More moving parts to operate and debug.

- Added latency on the request path.

- Requires solid platform maturity.

- Sidecars simplify applications but shift complexity to the platform.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Sidecars extend .NET services (e.g., via Dapr) for networking/security without code changes; run in the same pod in Kubernetes.

- 🎓 Middle: Use sidecars for cross-cutting concerns, such as tracing with OpenTelemetry or mTLS in ASP.NET Core integrate via tools like Envoy proxies.

- 👑 Senior: Decide when sidecars reduce duplication versus when they add unnecessary operational cost.

📚 Resources:

❓ What role does an API Gateway play in microservices?

An API Gateway acts as a single entry point (a "front door") for all external client requests. Instead of a mobile app or web browser calling dozens of individual microservices directly, they call the Gateway. The Gateway then routes the request to the correct internal service, aggregates the results, and returns them to the client.

What problems does an API Gateway solve?

- Hides internal architecture. Clients do not need to know how many services exist or how they are structured. Internal services can change without breaking clients.

- Centralizes cross-cutting concerns

The gateway commonly handles:- Authentication and authorization

- Rate limiting and throttling

- Request validation

- Logging and metrics

- SSL termination

- Reduces client complexity. Without a gateway, clients often need to call multiple services and coordinate responses. The gateway can aggregate responses or expose client-friendly APIs.

- Improves security. Internal services are not exposed to the public network. The gateway becomes a controlled boundary where security policies are enforced.

- Supports multiple client types. Different clients (web, mobile, partners) can be served through different gateway routes or even separate gateways.

What an API Gateway should not do

- It should not contain core business logic.

- It should not become a “god service” that everyone depends on.

- It should not replace proper service boundaries.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Understand that the Gateway is a Reverse Proxy. Know that it prevents "leaking" internal IP addresses/ports to the public internet and provides a single URL for the frontend to call.

- 🎓 Middle: Able to implement a Gateway using tools like YARP (Yet Another Reverse Proxy) or Ocelot. Understands the difference between a Gateway and a Load Balancer. Knows how to configure "BFF" (Backend for Frontend) patterns for different devices.

- 👑 Senior: Can discuss Resiliency Patterns (Retries, Circuit Breakers) at the Gateway level. Can architect for high availability so the Gateway isn't a single point of failure. Understands the trade-offs between "Service Mesh" (e.g., Istio/Linkerd) and "API Gateway."

📚 Resources:

❓ How do feature flags influence deployments and testing?

Feature flags decouple deployment from release. Deployment becomes a low-risk technical event (moving code to production), while release becomes a controlled business decision (turning code on for users).

Influence on Deployments

- Decoupling Deployment from Release: Feature flags allow code to be deployed to production in a "hidden" or "off" state. This means developers can push code frequently without immediately impacting end users.

- Gradual Rollouts (Canary Releases): They enable the gradual migration of traffic from a legacy system to a new service, which is essential for patterns like the Strangler Fig. You can help a new feature for a small percentage of users and increase that percentage as you gain confidence in the system's stability.

- Instant Rollbacks: If a new feature causes issues in production, it can be instantly disabled via a feature flag without requiring a new deployment or a rollback of the entire application.

- Reduced Risk: By gradually moving traffic, feature flags de-risk the process of switching traffic between services.

Influence on Testing:

- Testing in Production: Feature flags allow teams to safely test new services or features in the actual production environment with a limited subset of users or internal staff before a full release.

- A/B Testing: They facilitate running multiple versions of a feature simultaneously to gather data on user behavior and system performance.

- Environment Parity: Since code is deployed but not necessarily active, it helps maintain parity between development, staging, and production environments, as the same binaries can be used across all stages with different flag configurations.

C# example: feature flags in ASP.NET Core

Use Microsoft feature management.

dotnet add package Microsoft.FeatureManagement.AspNetCoreConfigure feature flags in appsettings.json

{

"FeatureManagement": {

"NewCheckoutFlow": false

}

}Register feature management in Program.cs

builder.Services.AddFeatureManagement();Use a feature flag in code. Controller example:

using Microsoft.FeatureManagement;

[ApiController]

[Route("checkout")]

public class CheckoutController : ControllerBase

{

private readonly IFeatureManager _featureManager;

public CheckoutController(IFeatureManager featureManager)

{

_featureManager = featureManager;

}

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> Checkout()

{

if (await _featureManager.IsEnabledAsync("NewCheckoutFlow"))

{

return Ok("New checkout flow");

}

return Ok("Old checkout flow");

}

}What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Feature flags allow code to be deployed without being active.

- 🎓 Middle: Use flags for gradual rollout, testing, and fast rollback.

- 👑 Senior: Enforce lifecycle management, observability, and flag hygiene.

📚 Resources:

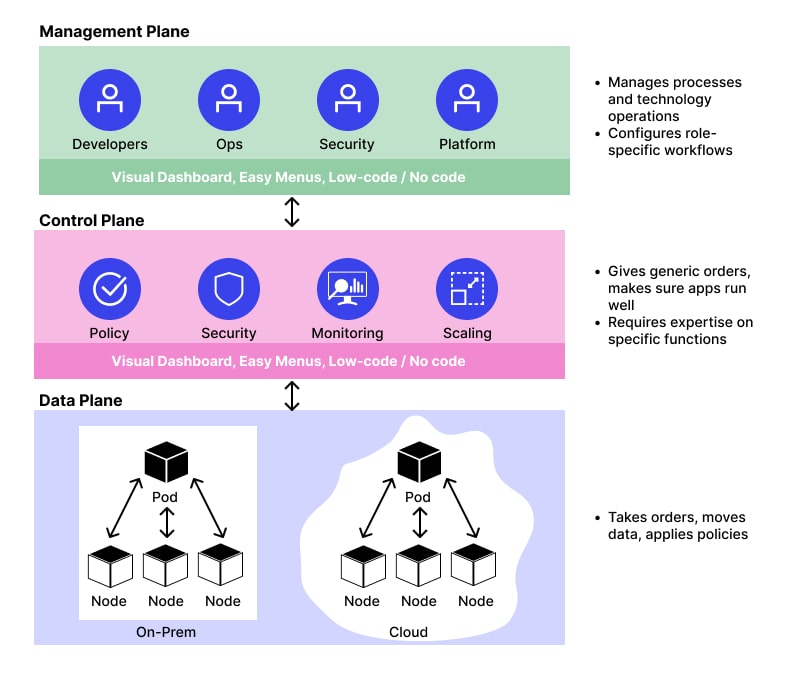

❓ What is a control plane vs a data plane in distributed systems?

The control plane and data plane split responsibilities between decision-making and execution. This separation helps systems scale, stay reliable, and evolve without changing business code.

Data plane

The data plane is responsible for handling real traffic and executing operations.

- Processes requests and responses.

- Moves data between services.

- Applies policies to live traffic.

- Must be fast, stable, and always available.

Examples:

- Service-to-service HTTP calls.

- Message consumption and processing.

- Sidecar proxies forwarding requests.

- Database read and write operations.

- The data plane is on the hot path. Any slowdown here affects users directly.

Control plane

The control plane manages configuration, policies, and coordination for the data plane.

- Defines routing rules and traffic policies.

- Manages service discovery and topology.

- Distributes configuration and certificates.

- Controls rollout, retries, timeouts, and security rules.

Examples:

- Service mesh controllers.

- API Gateway configuration.

- Kubernetes control components.

- Feature flag and traffic management systems.

The control plane is not in the request path. It changes behavior without touching application code.

How they work together

- The control plane sets rules and policies.

- The data plane enforces them at runtime.

- Changes in the control plane propagate safely to the data plane.

For example:

- A retry policy is defined in the control plane.

- Sidecars in the data plane apply it to live traffic.

Why this separation matters

- Safer changes without redeploying services.

- Centralized governance and consistency.

- Faster data paths with minimal logic.

- Better scalability and operational control.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Knows that the Data Plane is where the application code lives and traffic flows. Understands that infrastructure tools manage the "how."

- 🎓 Middle: Understands how service discovery and configuration providers (like Consul or Azure App Config) act as a control plane for their .NET apps.

- 👑 Senior: Can design for "Static Stability"—ensuring the data plane remains functional even if the control plane is unreachable. Able to choose between centralizing logic in a Gateway (Control) or a Sidecar (Data).

📚 Resources:

- Control Plane vs Data Plane: Key Differences Explained

- Control & Data Plane - How do They Differ?

- Difference between Control Plane and Data Plane

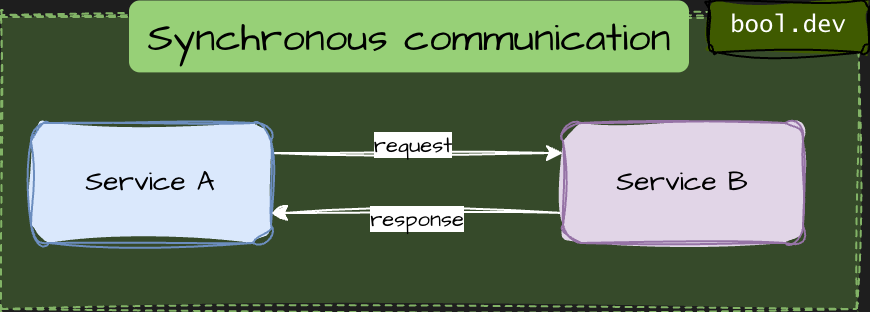

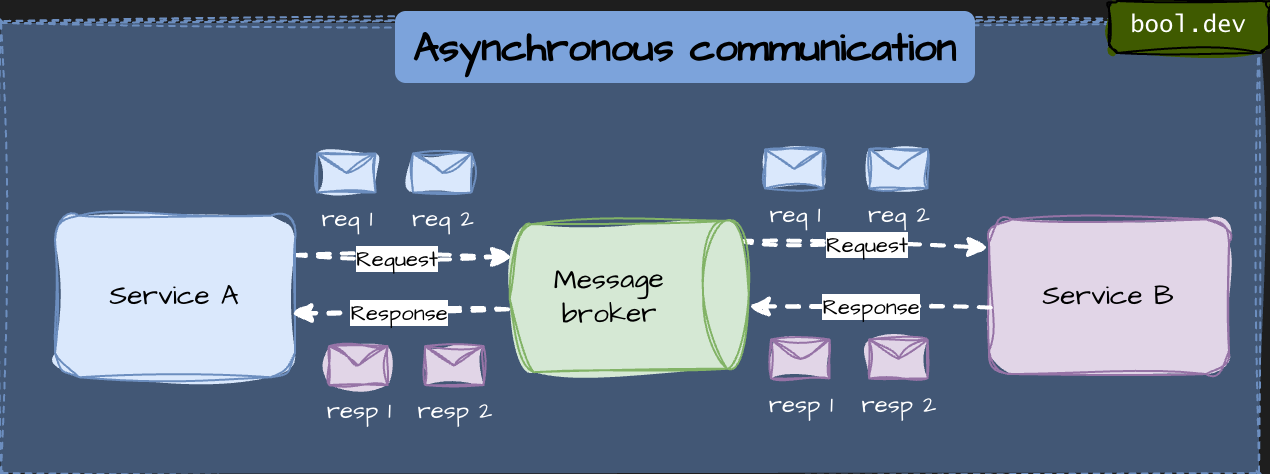

❓ What is the difference between synchronous and asynchronous service communication?

The difference is about waiting, coupling, and failure behavior.

Synchronous communication

- Caller waits for a response (HTTP, gRPC).

- Strong temporal coupling: both services must be available.

- Failures and latency propagate immediately.

- Best for user-facing requests and validations.

Asynchronous communication

- Caller sends a message and continues (events, queues).

- Loose temporal coupling: services do not need to be online at the same time.

- Better resilience and scalability.

- Best for background work and cross-service side effects.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Sync waits for a response, async does not.

- 🎓 Middle: Choose based on coupling, latency, and consistency needs.

- 👑 Senior: Combine both to avoid cascading failures and blocking workflows.

📚 Resources: Design interservice communication for microservices

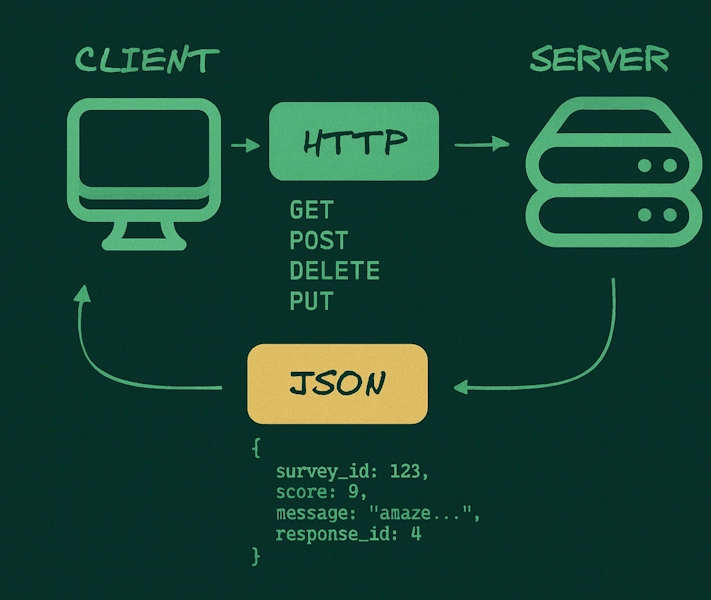

❓ When do you choose REST, gRPC, or messaging?

REST (HTTP + JSON)

A synchronous request–response style over HTTP using JSON. Simple, readable, and widely supported.

- Best for public APIs and browser or mobile clients.

- Easy to debug and integrate.

- Higher latency and larger payloads.

Use it when interoperability and simplicity matter most.

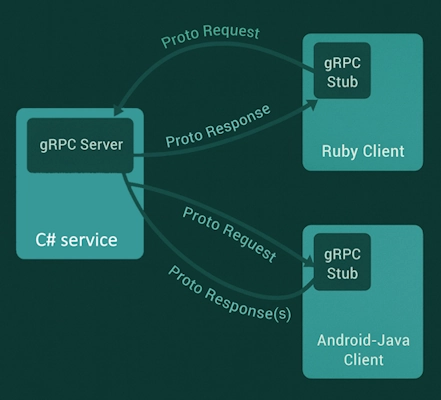

A high-performance synchronous RPC protocol over HTTP/2 using Protobuf. Strongly typed and optimized for service-to-service calls.

- Best for internal service-to-service communication.

- Low latency, small payloads, strong contracts.

- Requires shared schemas and client generation.

Use it when you control both sides and need performance.

Messaging (events, queues)

Asynchronous communication via a broker. Producers send messages or events without waiting for consumers.

- Best for async workflows and side effects.

- Decouples services in time and failures.

- No immediate response, eventual consistency.

Use it when work can happen later.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know what HTTP, gRPC, and messaging are and their basic use cases.

- 🎓 Middle: Choose based on latency, coupling, and ownership.

- 👑 Senior: Combine styles deliberately and avoid forcing one pattern everywhere.

❓ When should you use gRPC streaming?

Use gRPC streaming when data is continuous, incremental, or long-lived, and you want to avoid repeated request–response calls.

What gRPC streaming does is keep a single HTTP/2 connection open and sends multiple messages over it. Data flows as a stream instead of discrete requests.

When to use gRPC streaming

- Real-time updates

Live metrics, progress updates, notifications, status feeds. - Large datasets

Sending or receiving data in chunks instead of loading everything into memory. - High-frequency communication

Many small messages where HTTP request overhead would be wasteful. - Bidirectional workflows

Client and server exchange messages continuously (chat, coordination, control signals).

When not to use it

- Simple CRUD or short request–response calls.

- Public APIs or browser-first scenarios.

- When clients cannot reliably keep long-lived connections.

Types of gRPC streaming

- Server streaming: the client makes a single request, and the server streams responses.

- Client streaming: the client streams data; the server responds once.

- Bidirectional streaming: both streams are independent.

C# Example:

Use case: a client requests a report; the server streams progress updates.

Proto definition

syntax = "proto3";

service ReportService {

rpc GenerateReport(ReportRequest) returns (stream ReportProgress);

}

message ReportRequest {

string reportId = 1;

}

message ReportProgress {

int32 percent = 1;

string status = 2;

}Server-side implementation (ASP.NET Core)

public class ReportService : ReportService.ReportServiceBase

{

public override async Task GenerateReport(

ReportRequest request,

IServerStreamWriter<ReportProgress> responseStream,

ServerCallContext context)

{

for (int i = 0; i <= 100; i += 20)

{

await responseStream.WriteAsync(new ReportProgress

{

Percent = i,

Status = $"Progress {i}%"

});

await Task.Delay(500);

}

}

}Client-side consumption

var channel = GrpcChannel.ForAddress("https://localhost:5001");

var client = new ReportService.ReportServiceClient(channel);

using var call = client.GenerateReport(new ReportRequest

{

ReportId = "report-123"

});

await foreach (var update in call.ResponseStream.ReadAllAsync())

{

Console.WriteLine($"{update.Percent}% - {update.Status}");

}What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that streaming sends multiple messages over one connection.

- 🎓 Middle: Choose streaming for real-time or large data flows, not CRUD.

- 👑 Senior: Design backpressure, timeouts, and failure handling for long-lived streams.

📚 Resources: Create gRPC services and methods

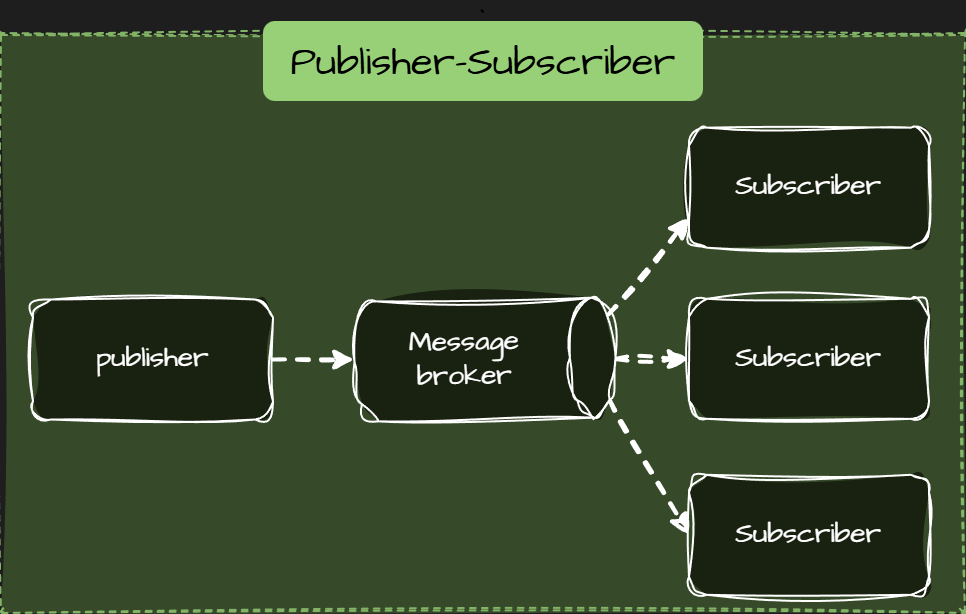

❓ Why are message brokers used in distributed systems?

message brokers are used to decouple services, improve reliability, and handle asynchronous work. They let services communicate without needing to be online or fast simultaneously.

Main reasons to use a message broker:

- Loose coupling. Producers send messages without knowing who consumes them. Services can evolve independently.

- Failure isolation. If a consumer is down, messages wait in the broker instead of failing requests or losing data.

- Asynchronous processing. Long-running or slow work moves out of the request path. Users get faster responses.

- Scalability. Consumers can scale horizontally and process messages in parallel.

- Traffic smoothing. Brokers absorb spikes—services process messages at their own pace.

- Reliable delivery. Most brokers support retries, acknowledgements, and dead-letter queues.

Typical use cases

- Event-driven architectures.

- Background jobs and workflows.

- Integration between bounded contexts.

- Audit logs and event streams.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Understands the "Fire and Forget" concept. Knows how to use a basic library like MassTransit or MediatR (for in-memory) to send a message.

- 🎓 Middle: Understands At-least-once vs. At-most-once delivery. Knows how to handle retries and move failing messages to a Dead Letter Queue.

- 👑 Senior: Designs for Idempotency (ensuring the same message processed twice doesn't break data). Can discuss the trade-offs between Queues (Point-to-point) and Topics (Pub/Sub) and can manage distributed transactions via the Saga Pattern.

📚 Resources: Event-driven architecture style

❓ What are at-least-once, at-most-once, and exactly-once delivery semantics?

This is a core concept in distributed systems and message queuing. Delivery semantics define the guarantee a message system provides about how many times a message will be delivered to a consumer, particularly in the presence of failures.

Here are the three standard delivery semantics:

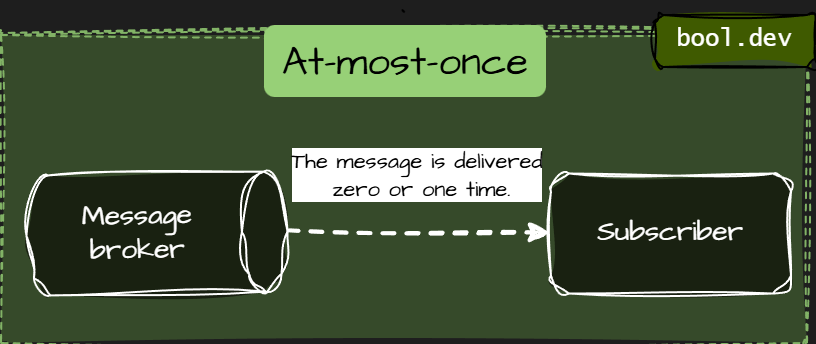

At-most-once

- The message is delivered zero or one time.

- No retries. If delivery fails, the message is lost.

- Fast and simple, but unreliable.

- Use it when occasional loss is acceptable (logs, metrics).

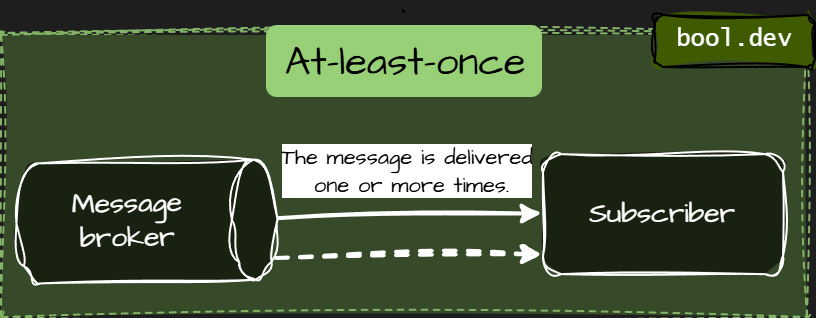

At-least-once

- The message is delivered one or more times.

- Retries are allowed. Duplicates can happen.

- The most common and practical model.

- Use it when correctness matters, and consumers can handle duplicates.

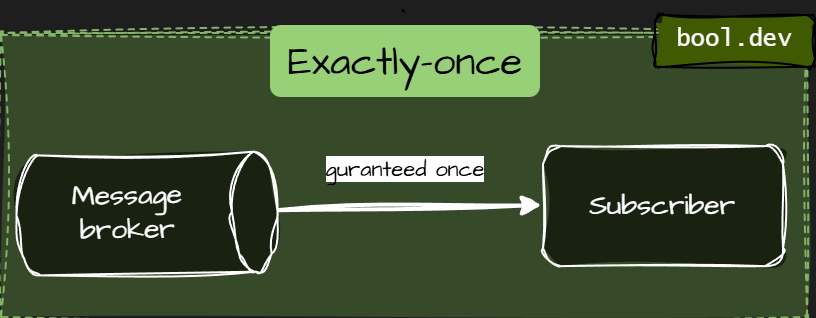

Exactly-once

- The message is delivered once and only once.

- No loss, no duplicates.

- Very hard and expensive to achieve in distributed systems.

- Usually implemented as at-least-once + idempotency, not actual magic delivery.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Messages may be lost or duplicated depending on the guarantee.

- 🎓 Middle: Design consumers to be idempotent and safe for retries.

- 👑 Senior: Choose semantics consciously and design end-to-end consistency, not just broker settings.

📚 Resources: At most once, at least once, exactly once

❓ How do you ensure idempotency in a .NET message consumer?

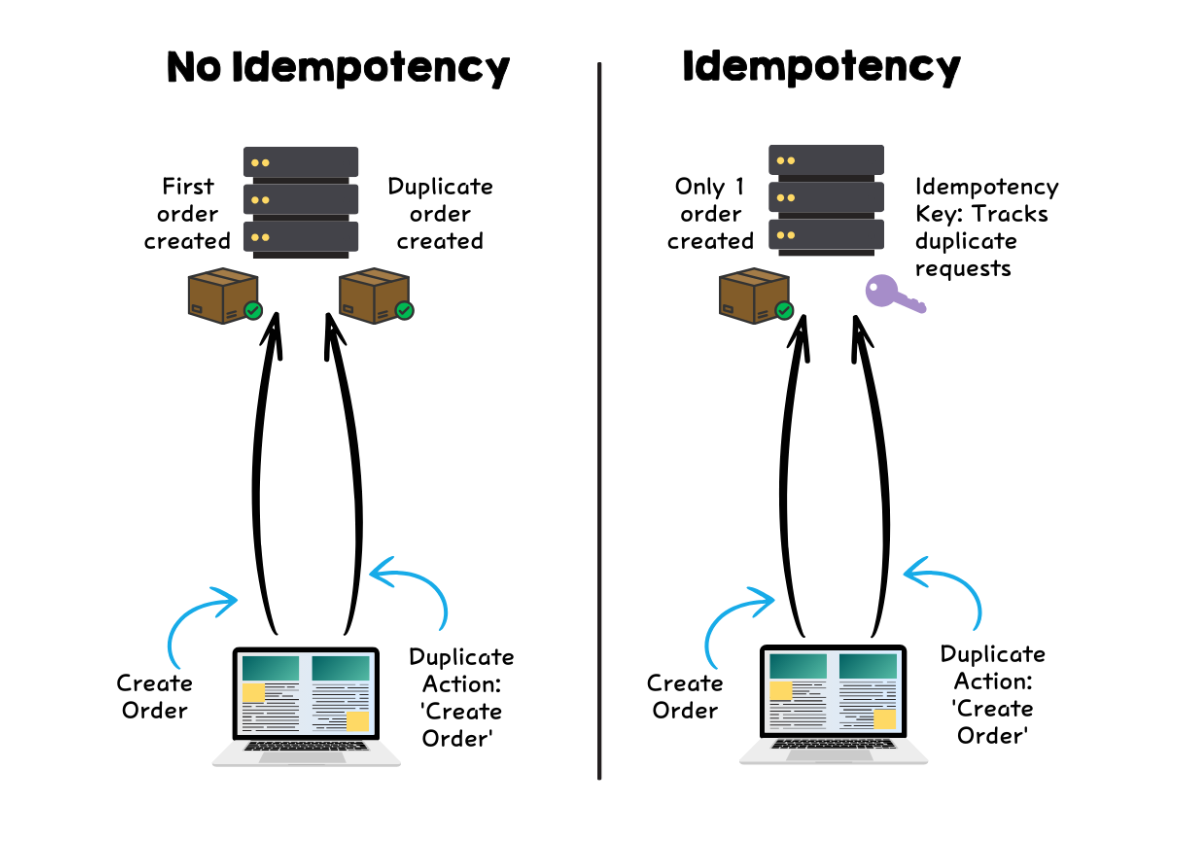

Idempotency means that processing the same message multiple times produces the same result. This is required because most brokers use at least one delivery.

Core techniques to handle idempotency:

- Message ID deduplication. Store processed message IDs and skip duplicates.

- Idempotent writes. Design database operations so that repeating them does not change the outcome.

- Atomic processing. Persist side effects and the “processed” marker in one transaction.

- Natural idempotency. Use business keys (OrderId, PaymentId) instead of auto-generated IDs.

Simple C# example (deduplication)

public async Task HandleAsync(OrderCreated message)

{

if (await _db.ProcessedMessages.AnyAsync(x => x.Id == message.MessageId))

return;

using var tx = await _db.Database.BeginTransactionAsync();

_db.Orders.Add(new Order

{

OrderId = message.OrderId,

Total = message.Total

});

_db.ProcessedMessages.Add(new ProcessedMessage

{

Id = message.MessageId,

ProcessedAt = DateTime.UtcNow

});

await _db.SaveChangesAsync();

await tx.CommitAsync();

}Common mistakes

- Relying on the broker for exactly-once delivery.

- Deduplicating in memory instead of persistent storage.

- Using side effects before marking the message as processed.

- Forgetting idempotency for retries after partial failures.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Messages may arrive multiple times and must be handled safely.

- 🎓 Middle: Use message IDs, transactions, and idempotent writes.

- 👑 Senior: Design end-to-end idempotency across services, storage, and workflows.

📚 Resources:

❓ What is the Competing Consumers pattern, and when is it useful?

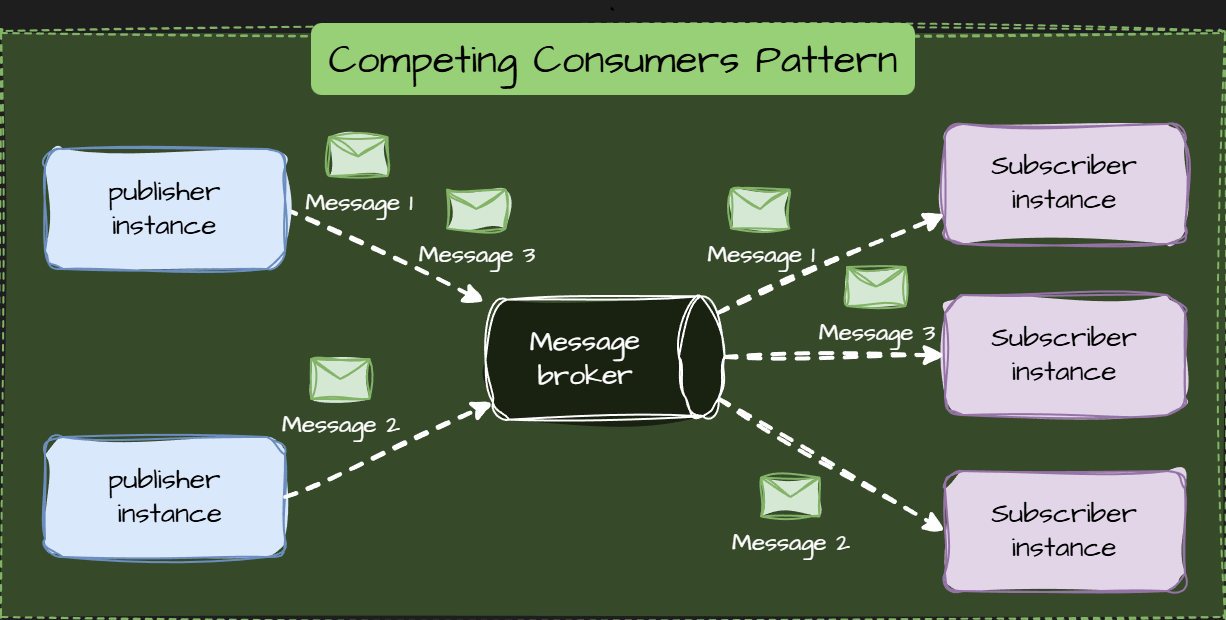

The Competing Consumers pattern involves multiple instances of the same service (consumers) listening to a single message queue. When a message arrives, the broker ensures that only one consumer receives and processes it. The consumers "compete" for the next available task, allowing the system to process many messages in parallel.

How It Works

- Producer: Sends messages (tasks) to a single message queue.

- Queue/Broker: Stores the messages and acts as a buffer. It handles load balancing by ensuring messages are distributed efficiently among the available consumers.

- Consumers (The Pool): Multiple instances of the same consumer application run in parallel. When one consumer finishes a task, it immediately polls the shared queue for the following available message. The queue marks the message as locked or invisible until the receiving consumer acknowledges its processing, preventing other consumers from picking it up.

Why use it?

- High Throughput: It allows you to process a large volume of messages faster by distributing the work across multiple worker instances.

- Scalability: You can dynamically scale the number of consumers based on the queue size (auto-scaling).

- Resiliency: If one consumer instance crashes while processing, the broker can return the message to the queue for another consumer to handle.

Key Trade-Offs

- Message Ordering is Not Guaranteed: Since multiple consumers process messages concurrently, the order in which messages are processed is generally not guaranteed to be FIFO (First-In, First-Out).

- Idempotency Required: Because of "at-least-once" delivery, a consumer might receive the same message twice. The code must be safe to run multiple times with the same input.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Understands that adding more instances of a worker service speeds up message processing. Knows the difference between Competing Consumers and Pub/Sub.

- 🎓 Middle: Knows how to configure Prefetch Count (how many messages a consumer grabs at once) to prevent one worker from being overwhelmed while others are idle. Understands the "Visibility Timeout" or "Lock" period.

- 👑 Senior: Can solve the Ordering Problem using techniques like Message Sessions (Azure Service Bus) or Partitioning (Kafka/RabbitMQ Sharding) when sequential processing is required within a specific context (e.g., per user).

📚 Resources: Competing Consumers Pattern

❓ What is a Dead Letter Queue, and how do you design reprocessing logic?

A Dead Letter Queue (DLQ) is a special queue where messages are sent when they cannot be processed successfully. Instead of blocking the main flow or losing data, failed messages are isolated for later analysis and recovery.

DLQs are common in message-driven systems using Azure Service Bus, RabbitMQ, Kafka, or AWS SQS.

Reprocessing involves two phases:

1. Automatic Retries (In-Queue)

This handles transient failures (e.g., connection timeouts).

- Mechanism: The message broker retries delivery a fixed number of times (e.g., 3-5).

- Strategy: Use exponential backoff between retries to avoid overwhelming a struggling dependency.

- Goal: Resolve temporary issues before the message is exiled to the DLQ.

2. Manual/Scheduled Reprocessing (From DLQ)

This handles permanent failures (e.g., data bugs, sustained dependency outages).

- Strategy: Messages remain in the DLQ until the root cause is confirmed to be fixed.

- Manual Fix: A developer inspects the message, fixes the code or data, and manually pushes the message back to the main queue.

- Scheduled Job: A batch process periodically attempts to re-queue the messages, typically after a known external outage has resolved.

Key Principle: Never automatically re-queue from the DLQ without confirming the original error has been resolved, as this risks creating a retry loop.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that DLQ stores messages that failed processing and protects the main flow.

- 🎓 Middle: Understand retry strategies, idempotency, and when to reprocess messages.

- 👑 Senior: Design safe replay mechanisms, classify failures, and ensure observability and back-pressure control.

📚 Resources:

- Transient fault handling

- Using dead-letter queues in Amazon SQS

- Overview of Service Bus dead-letter queues

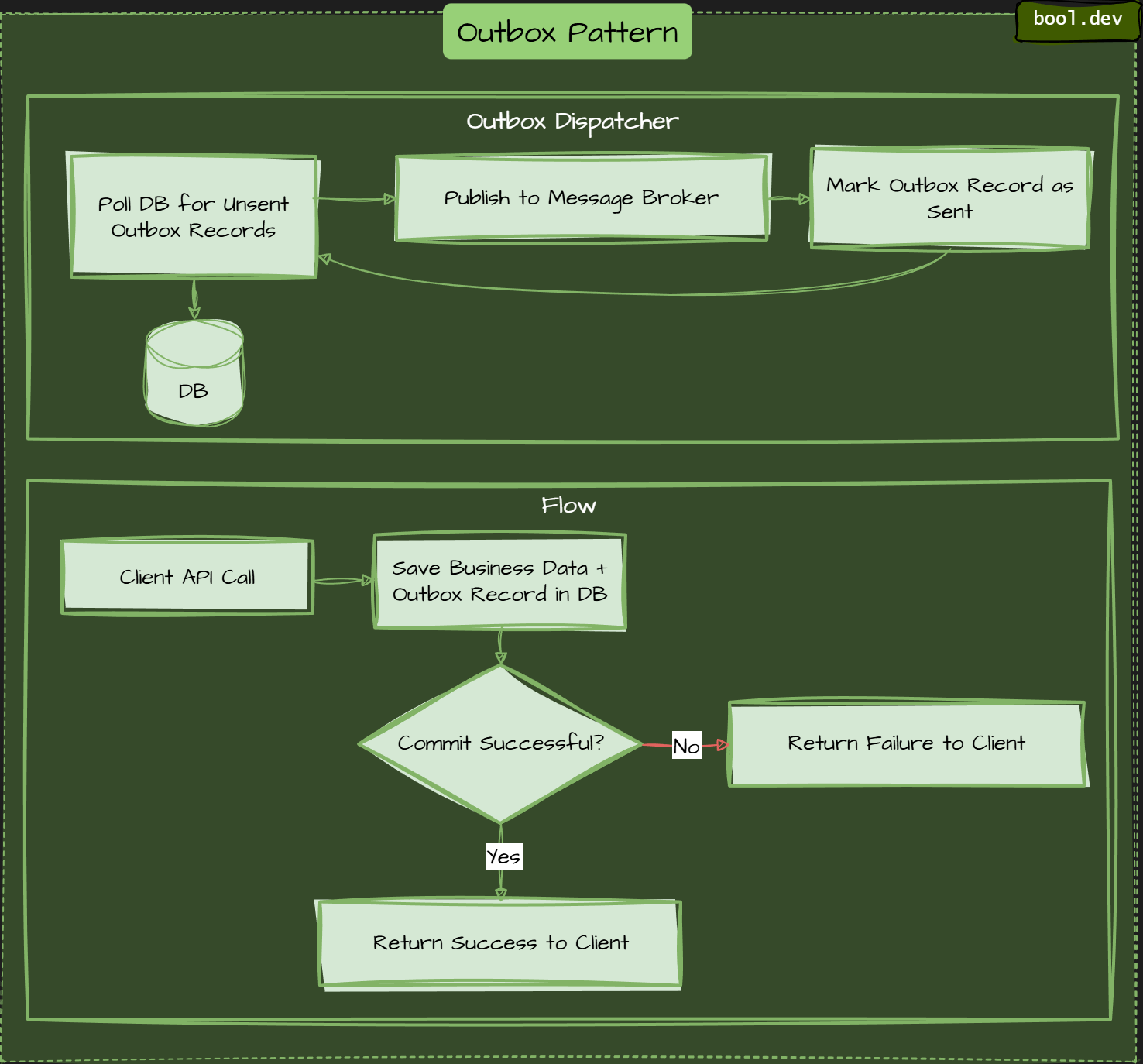

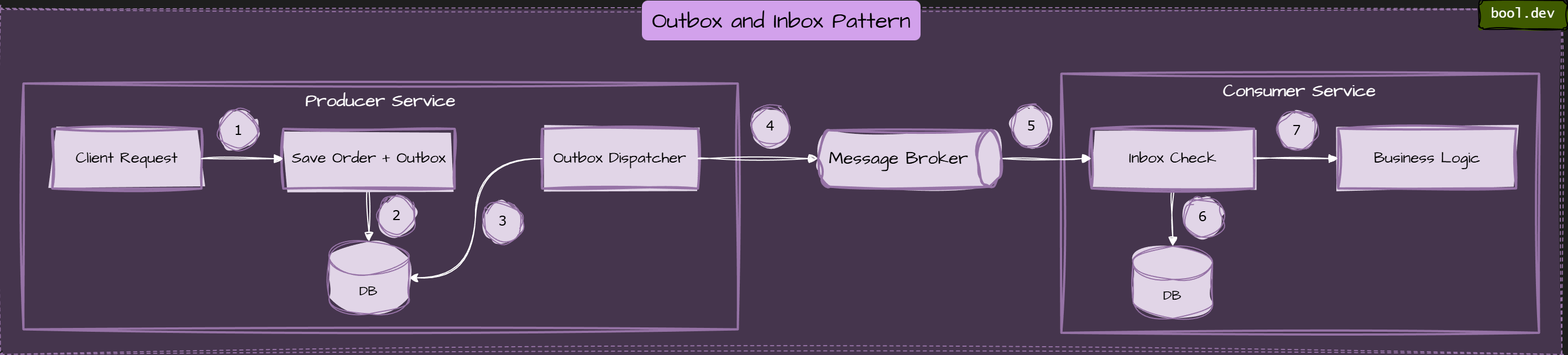

❓ What is the Outbox pattern, and why do distributed systems rely on it?

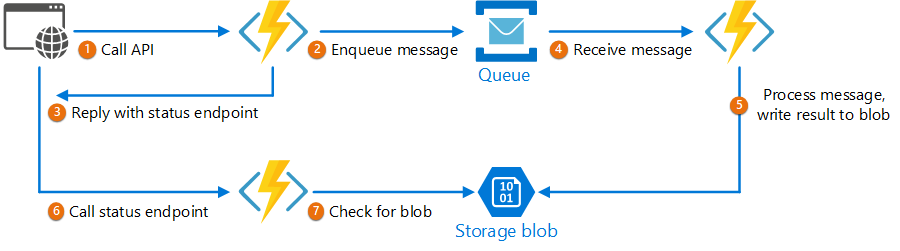

The Outbox pattern is a reliability pattern that guarantees messages or events are published only after the local database transaction commits. It solves the classic problem where data is saved successfully, but the message meant to notify other services is lost. In distributed systems, this pattern is critical for consistency.

Outbox dispatcher runs separately, picks up pending messages, publishes them, marks them as sent.

Without Outbox, a service usually does this:

- Save data to the database.

- Publish an event to a message broker.

If the process crashes between these steps, the system becomes inconsistent. Data is stored, but no event is sent. Other services never find out. The Outbox pattern removes this gap.

How the Outbox pattern works:

- Write business data and the outbox record in one transaction. The service saves Domain changes (orders, payments, users) in an Outbox record containing the event payload. Both writes happen in the same database transaction.

- Commit the transaction. If the commit succeeds, both the data and the event are safely stored.

- Publish asynchronously. A background process reads Outbox records and publishes them to the message broker.

- Mark as published. After successful publishing, the Outbox record is marked as sent or removed.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that Outbox prevents lost messages after DB commits.

- 🎓 Middle: Implement Outbox with background publishing and retries.

- 👑 Senior: Combine Outbox with Inbox, idempotency, and monitoring for complete reliability.

📚 Resources: Transactional Inbox and Outbox Patterns: Practical Guide for Reliable Messaging

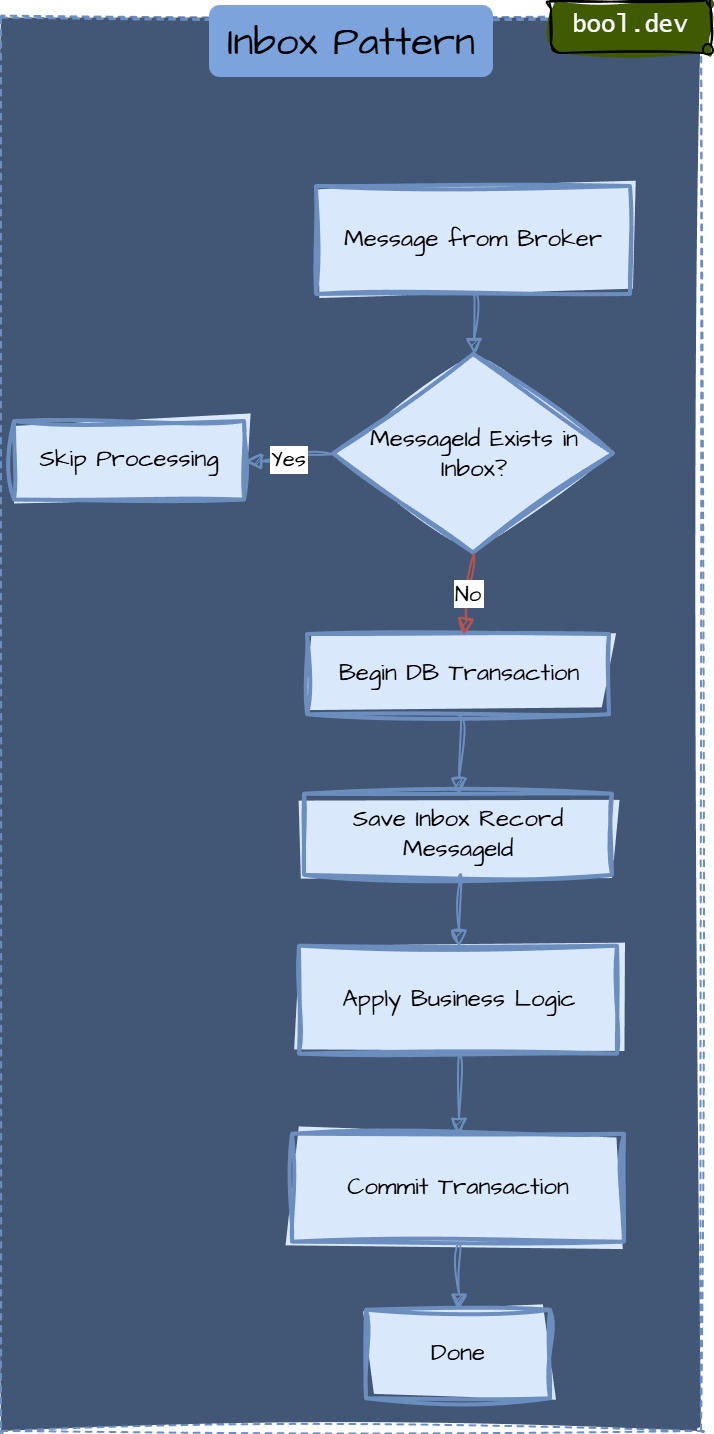

❓ What is the Inbox pattern, and how does it support end-to-end consistency?

Inbox pattern ensures that a message received by a consumer service is processed and recorded atomically with the consumer's state change, preventing message loss or duplicate processing.

The Inbox pattern helps achieve end-to-end consistency by:

- Preventing duplicate side effects when messages are retried.

- Ensuring that business operations are applied only once.

- Allowing safe retries after crashes or timeouts.

- Making message handling deterministic and repeatable.

Inbox vs Outbox

- Inbox: protects consumers from duplicate processing.

- Outbox: protects producers from losing messages after database commits.

They are often used together to build reliable event-driven flows.

Common mistakes

- Not storing Inbox records transactionally with business changes.

- Using in-memory caches instead of durable storage.

- Letting the Inbox table grow without retention or cleanup.

- Treating the inbox as optional while assuming exactly-once delivery.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that Inbox prevents duplicate message processing.

- 🎓 Middle: Understand how Inbox works with transactions and retries.

- 👑 Senior: Design Inbox storage, retention, and integration with Outbox for end-to-end consistency.

📚 Resources: Transactional Inbox and Outbox Patterns: Practical Guide for Reliable Messaging

❓ How do you handle validation of API/Contract changes across microservices?

API and contract changes are one of the main failure points in microservices. Services are deployed independently, so you must assume that producers and consumers will run different versions simultaneously. Validation is about proving that a change is safe before it reaches production.

1. Consumer-Driven Contract Testing (PACT testing)

This is the most effective way to ensure a service doesn't break its consumers.

Instead of the Provider (API creator) defining what's essential, the Consumer defines a "Pact" file containing the exact requests it sends and the responses it expects.

Validation: During the Producer's CI/CD pipeline, the Pact tests are run. If a proposed code change breaks a consumer's expected contract, the build fails.

Benefit: You find out an API change will break a specific mobile app or microservice before you deploy.

2. Schema Registry (for Asynchronous/Events)

For services communicating via Kafka, RabbitMQ, or Azure Service Bus using Protobuf or Avro.

The Registry: A central service (like Confluent Schema Registry or Azure Event Grid Schema Registry) stores all versions of your contracts.

Enforcement: The registry is configured with a Compatibility Level (e.g., BACKWARD or FULL).

Validation: When a producer tries to publish an event with a new schema, the Registry validates it against previous versions. If it violates compatibility rules (e.g., removing a required field), the Registry rejects the schema.

3. Breaking Change Policy (Semantic Versioning)

Establish a strict "No Breaking Changes" rule for existing endpoints.

Expansion only: You can add new fields or endpoints, but never rename or delete existing ones.

Versioning: If a breaking change is unavoidable, you must version the API (e.g., /api/v1/orders vs /api/v2/orders).

Parallel Run: Run both versions in production simultaneously. Use monitoring to see when traffic to v1 drops to zero before decommissioning it.

4. Integration Tests in CI/CD

Use tools like Swagger/OpenAPI to generate documentation. Use tools like spectral or oasdiff in your CI pipeline to automatically detect breaking changes in the specification file itself compared to the version currently in production.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that API contracts must stay backward compatible.

- 🎓 Middle: Use contract tests and schema validation in CI.

- 👑 Senior: Define compatibility rules, tooling, and rollout strategies across teams.

📚 Resources:

❓ How do MassTransit or NServiceBus simplify messaging compared to raw clients?

MassTransit and NServiceBus sit on top of raw brokers like Azure Service Bus or RabbitMQ. Instead of working with low-level queues and messages, you work with typed messages and consumers, with most reliability concerns handled for you.

What do you handle with raw clients

- Serialization and deserialization.

- Retries and transient failures.

- Poison messages and DLQs.

- Idempotency and duplicate delivery.

- Correlation IDs and tracing.

This logic is often reimplemented differently across services.

What messaging frameworks give you

- Strongly typed consumers instead of low-level handlers.

- Built-in retries, delayed retries, and error queues.

- Inbox and Outbox support for safe message processing.

- Transport abstraction (Azure Service Bus, RabbitMQ, SQS).

- Consistent observability and message routing.

Trade-offs

- Added abstraction and learning curve.

- Broker-specific features are sometimes hidden.

When they make sense

- Multiple services rely on messaging.

- Reliability and consistency matter.

- Teams want shared conventions and fewer mistakes.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Frameworks reduce messaging boilerplate.

- 🎓 Middle: They handle retries, errors, and idempotency.

- 👑 Senior: Choose frameworks when consistency matters more than low-level control.

📚 Resources:

❓ How do you avoid temporal coupling between producers and consumers?

Temporal coupling happens when a producer and a consumer must be available at the same time for the system to work. If one side is down or slow, the whole flow breaks. In distributed systems, this quickly becomes a reliability and scalability problem.

Example of Temporal coupling

Sequential Dependencies: When methods or operations must be called in a specific order to work correctly, without explicit enforcement of that order.

# Problematic: Temporal coupling through required sequence

user_service = UserService()

user_service.initialize_connection() # Must be called first

user_service.authenticate() # Must be called second

user_service.load_preferences() # Must be called third

user_service.get_user_data() # Only works after all aboveCommon mistakes

- Long synchronous call chains across services.

- Using messaging but waiting for an immediate reply.

- Treating message brokers like remote procedure calls.

Ways to reduce temporal coupling

- Use asynchronous messaging. Instead of synchronous HTTP calls, publish events to a message broker. The producer writes once and moves on. Consumers process when they are ready.

- Persist messages durably. Queues and topics must store messages until consumers can handle them. This protects against downtime and restarts.

- Avoid request-response dependencies. Do not build workflows that require an immediate response from another service to continue. Prefer eventual consistency.

- Design idempotent consumers. If messages are retried or delivered later, consumers must handle duplicates safely.

- Use timeouts and fallbacks. When synchronous calls are unavoidable, always use timeouts, retries, and graceful degradation rather than blocking.

- Separate commands from queries. Commands can be async and fire-and-forget. Queries can stay synchronous but should not mutate.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that async messaging decouples services in time.

- 🎓 Middle: Design event-driven flows and idempotent consumers.

- 👑 Senior: Balance async and sync communication and avoid hidden dependencies.

📚 Resources:

- Design Smell: Temporal Coupling

- Temporal Coupling in Software Development: Understanding and Prevention Strategies

Distributed Data and State Management

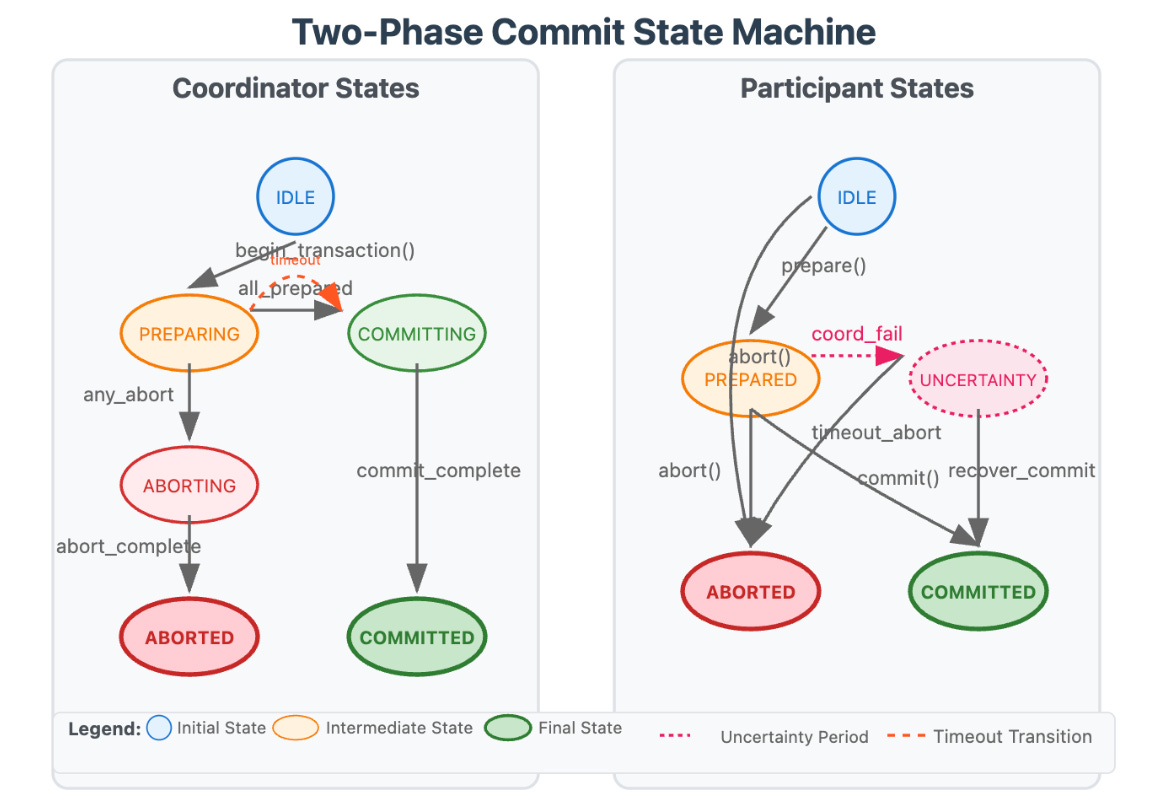

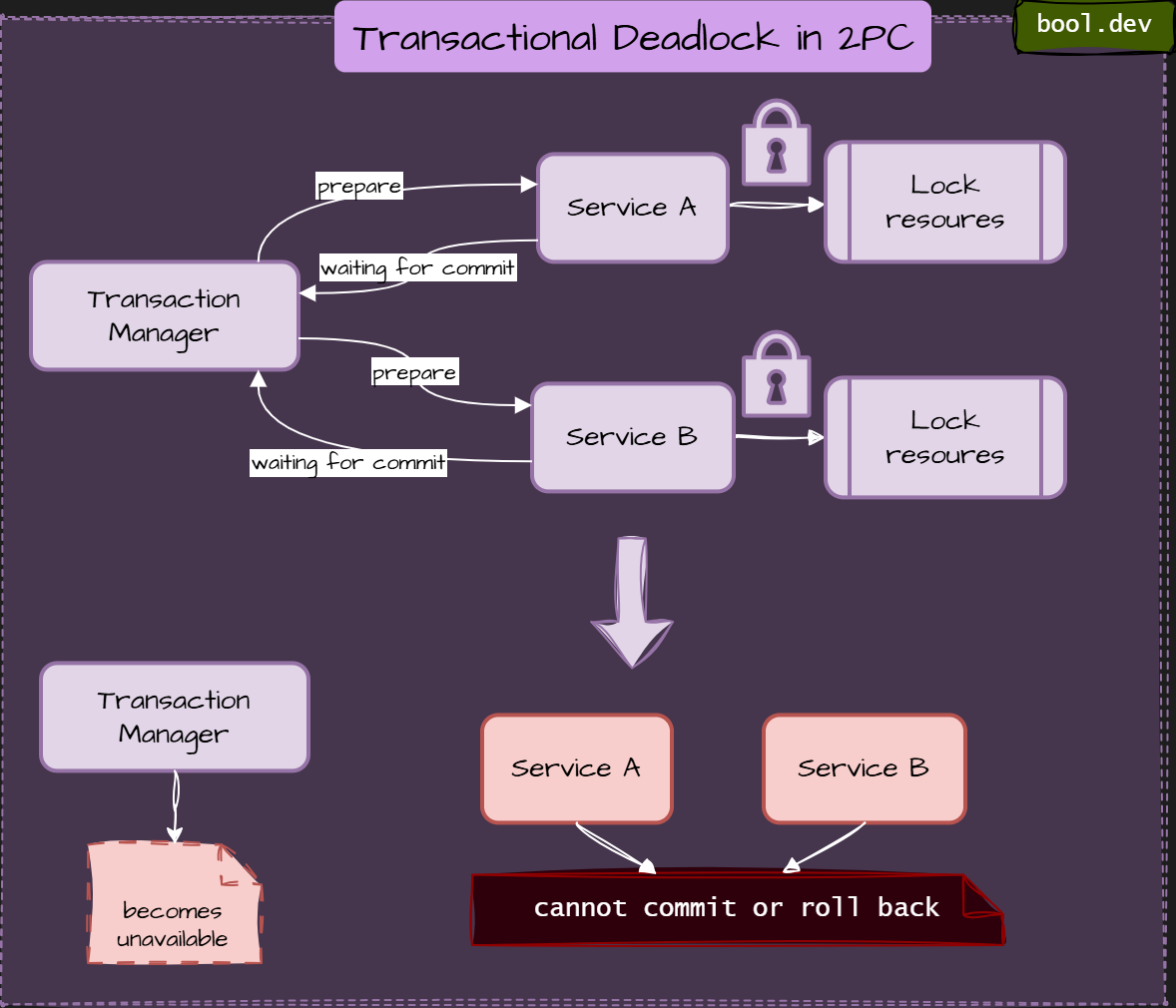

❓ Why is 2PC avoided in microservices, and what are the alternatives?

Two-Phase Commit (2PC) is a distributed transaction protocol that tries to guarantee atomicity across multiple services or databases. In microservices, it is usually avoided because it creates tight coupling, hurts availability, and does not scale well.

Common alternatives to 2PC

Saga pattern

A Saga splits a transaction into multiple local transactions. Each step commits independently. If something fails, compensating actions undo previous steps.

- Orchestration: a central coordinator drives the steps.

- Choreography: services respond to events and advance the process.

Eventual consistency

Instead of immediate consistency, systems accept temporary inconsistency and converge over time using events and retries.

Outbox and Inbox patterns

- Outbox ensures messages are published reliably after local database commits.

- Inbox ensures messages are processed exactly once at the consumer level.

Together, they give transactional safety without distributed locks.

Idempotent operations

Consumers handle duplicate messages safely, allowing retries without corruption.

Domain redesign

Often, the real fix is better boundaries. If multiple services must commit together, they may belong to the same bounded context.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that 2PC blocks services and hurts reliability.

- 🎓 Middle: Use Sagas and eventual consistency instead of distributed transactions.

- 👑 Senior: Design domains to avoid cross-service transactions and apply compensations safely.

📚 Resources:

- Design Microservices: Using DDD Bounded Contexts

- [ru] Choreography pattern

- Transactional Inbox and Outbox Patterns: Practical Guide for Reliable Messaging

❓ How do you implement a saga, and how do compensating steps work?

A Saga is a sequence of local transactions where each service performs its task and then publishes an event to trigger the next service. If any step fails, the Saga executes Compensating Transactions to undo the previous successful steps, ensuring eventual consistency.

The key idea: move from atomic transactions to controlled business rollback.

How a Saga works

- Execute a local transaction. Each service performs its own database transaction and commits it.

- Publish an event or command. After committing, the service notifies the next step in the process.

- Continue the flow. Other services react and execute their local transactions.

- Handle failure with compensation. If a step fails, previously completed steps are compensated in reverse order.

The two typical saga implementation approaches are choreography and orchestration. Each approach has its own set of challenges and technologies to coordinate the workflow.

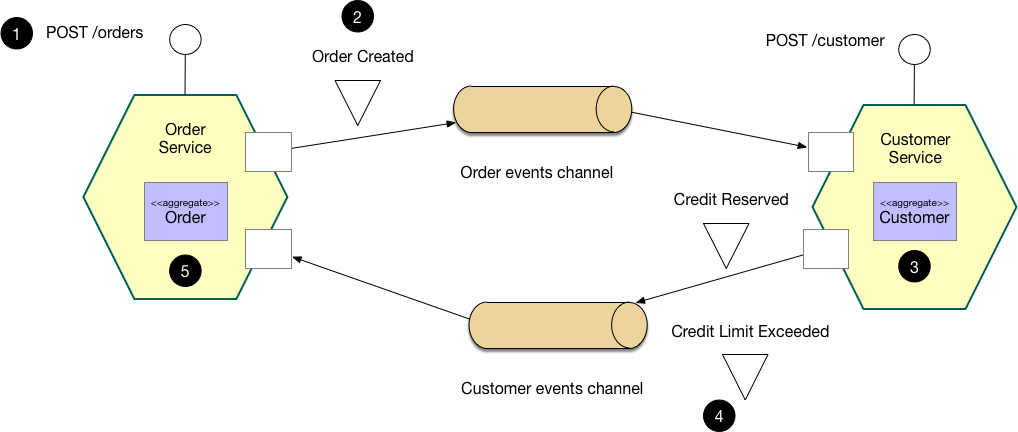

Example: Choreography-based saga (decentralized)

In the choreography approach, services exchange events without a centralized controller. With choreography, each local transaction publishes domain events that trigger local transactions in other services.

Best For: Simple workflows with few services.

Cons: Hard to track the overall state of the process; can become a "spaghetti" of events.

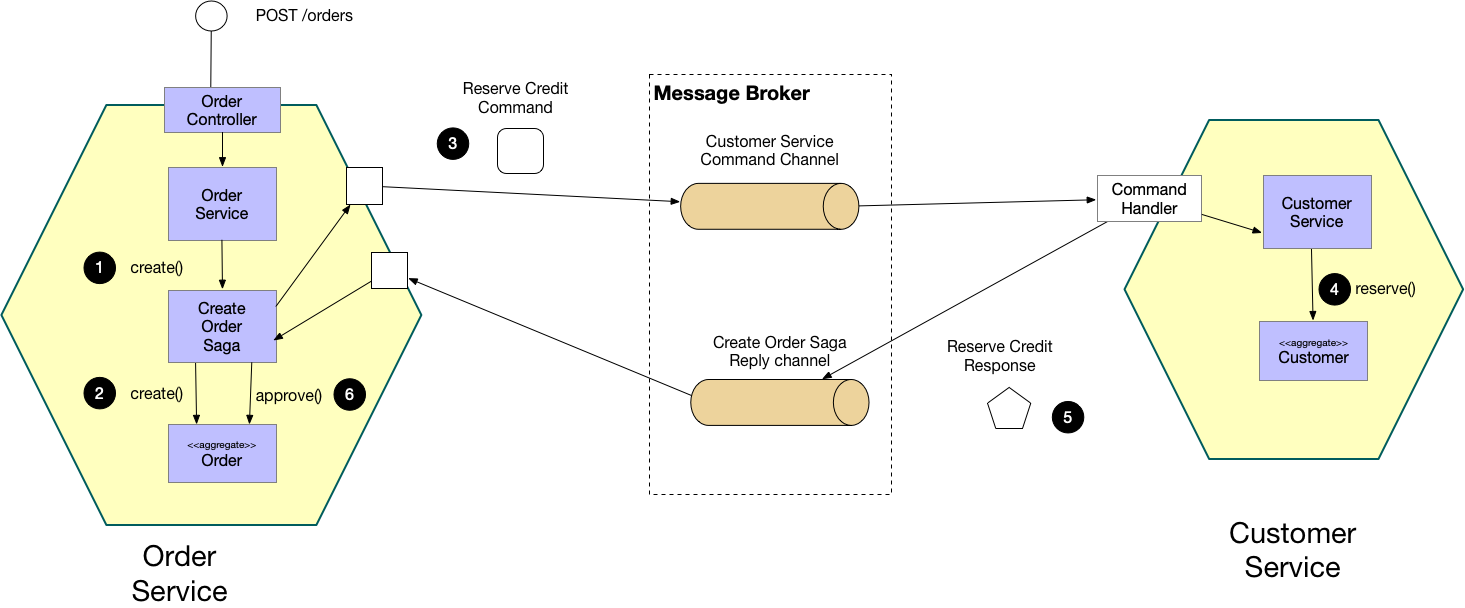

Example: Orchestration-based saga (Centralized)

In orchestration, a centralized controller, or orchestrator, handles all the transactions and tells the participants which operation to perform based on events. The orchestrator processes saga requests, stores and interprets each task's state, and handles failure recovery using compensating transactions.

Best For: Complex workflows with many steps or conditional logic.

Cons: The Orchestrator can become a single point of failure or a bottleneck if not appropriately scaled.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that a Saga replaces distributed transactions with local steps and compensation.

🎓 Middle: Implement Saga flows and design proper compensating actions.

👑 Senior: Choose orchestration or choreography wisely and ensure observability and safety.

📚 Resources:

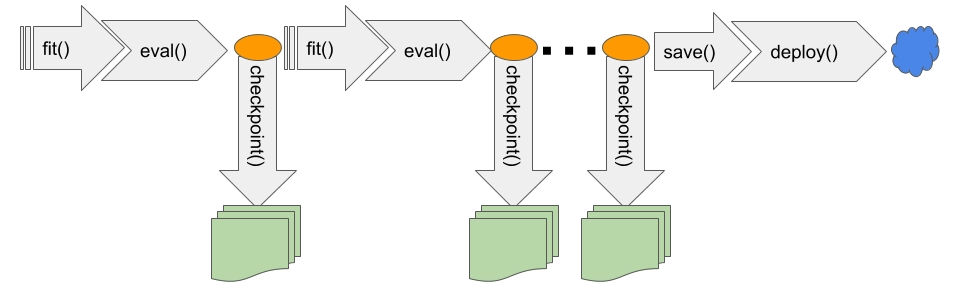

❓ When would you avoid event sourcing in enterprise systems?

While Event Sourcing (storing every state change as a sequence of events) is powerful for auditing and complex domains, it introduces significant complexity that can derail an enterprise project if misapplied.

You should avoid Event Sourcing in the following scenarios:

- Simple CRUD domains. If the system is mostly create, read, update, and delete with no complex workflows, event sourcing adds overhead with little value.

- Low business value from history. If the business does not care about full change history, replay, or temporal queries, storing every event is unnecessary.

- Heavy reporting requirements. Building reports over event streams requires projections, rebuilds, and operational discipline. Traditional read models are often simpler and faster.

- Complex data corrections. Fixing insufficient data in event-sourced systems is hard. You cannot “just update a row. Corrections require compensating events or stream rewriting, which many teams struggle with.

- Tight delivery timelines. Event sourcing has a steep learning curve. Teams new to it often slow down significantly and make costly mistakes early.

- Integration-heavy systems. When many external systems expect the current state, not event streams, you still end up maintaining state projections everywhere.

- Limited team maturity. Event sourcing requires strong discipline around versioning, idempotency, replay safety, and schema evolution. Without this, systems become fragile.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that event sourcing is advanced and not a default choice.

- 🎓 Middle: Recognize when CRUD plus events is enough.

- 👑 Senior: Push back on unnecessary event sourcing and choose it only when business value is clear.

📚 Resources:

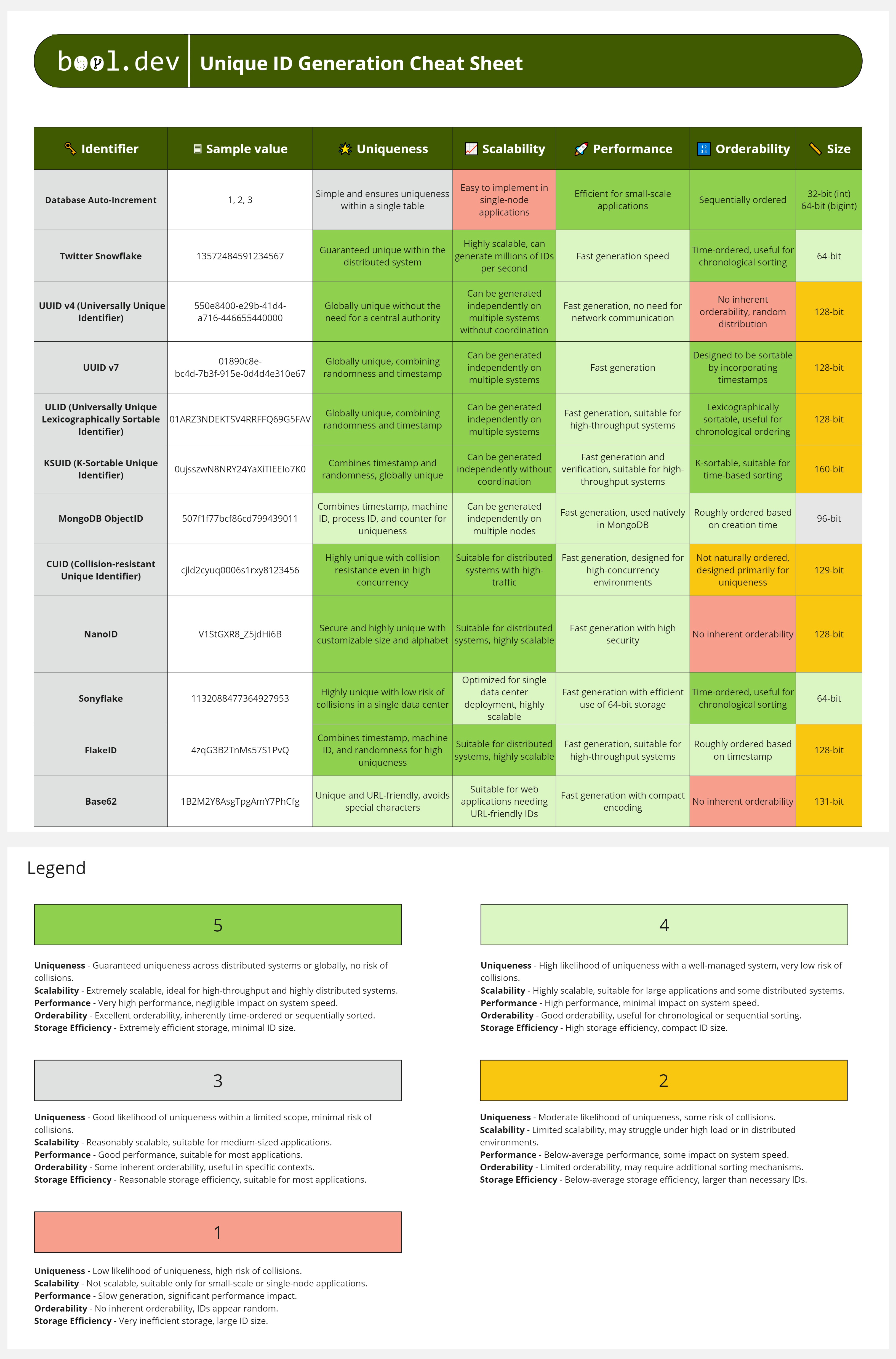

❓ How do you choose distributed IDs, and which IDs are best?

Distributed IDs must be unique across services, generated without coordination, and safe under scale. The wrong choice causes collisions, hot partitions, or performance problems. There is no single “best” ID. The right one depends on your access patterns and infrastructure.

What matters when choosing an ID:

- Global uniqueness without central coordination.

- Fast generation under high load.

- Good databases and index behavior.

- Safe exposure outside the system (URLs, APIs).

- Optional ordering by time.

The Main Candidates:

1. UUID / GUID (v4)

Standard 128-bit random identifiers.

- Pros: Guaranteed to be unique across any system without coordination. No collision risk.

- Cons: Not sortable. Because they are random, inserting them into a clustered index (like in SQL Server or MySQL) causes "index fragmentation," severely hurting write performance. They are also bulky (36 characters as strings).

- Best For: Non-database identifiers, session IDs, or distributed systems where insert order doesn't matter.

2. Snowflake IDs (Twitter/Discord style)

64-bit integers composed of a timestamp, worker ID, and sequence number.

- Pros: Time-sortable. Since the first bits are a timestamp, new IDs are always larger than old ones. This keeps database indexes healthy. They are smaller than UUIDs (64 bits vs 128 bits).

- Cons: Requires a "Coordinator" (like Zookeeper or a central configuration) to assign unique Worker IDs to each node to prevent collisions.

- Best For: High-scale systems like Twitter or Discord where chronological sorting is vital.

3. ULID (Universally Unique Lexicographically Sortable Identifier)

A 128-bit identifier that combines a timestamp with randomness.

- Pros: Lexicographically sortable (sortable as strings). Compatible with UUID storage formats and resolves fragmentation—no coordination required between nodes.

- Cons: Slightly larger than Snowflake IDs; can still lead to "hotspots" in the database if many IDs are generated at the exact millisecond.

- Best For: Modern web apps needing the convenience of UUIDs with the performance of sortable keys.

Practical suggestions:

- Prefer UUID v7 or Snowflake-style IDs for most distributed systems.

- Avoid using UUID v4 as a clustered primary key in write-heavy databases.

- Never expose internal numeric IDs to external clients without proper authorization.

- Generate IDs at the service boundary, not in shared infrastructure.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that IDs must be unique and not coordinated.

- 🎓 Middle: Understand index impact and ordering trade-offs.

- 👑 Senior: Choose IDs based on scale, storage, and domain exposure.

📚 Resources: Unique ID Generation Cheat Sheet

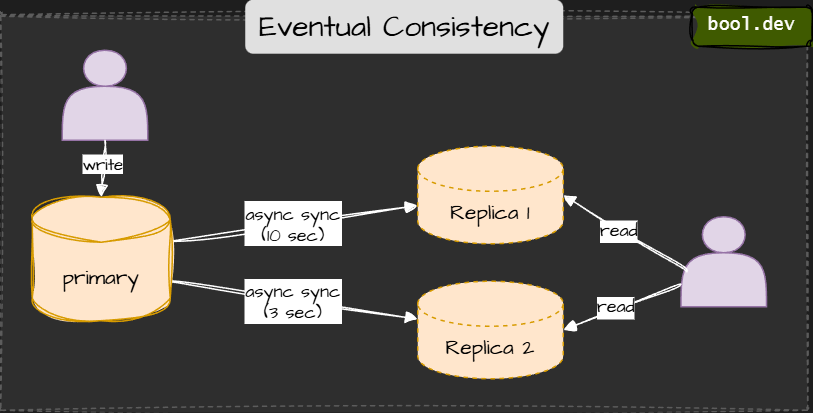

❓ What is eventual consistency, and how do you communicate its impact to the business?

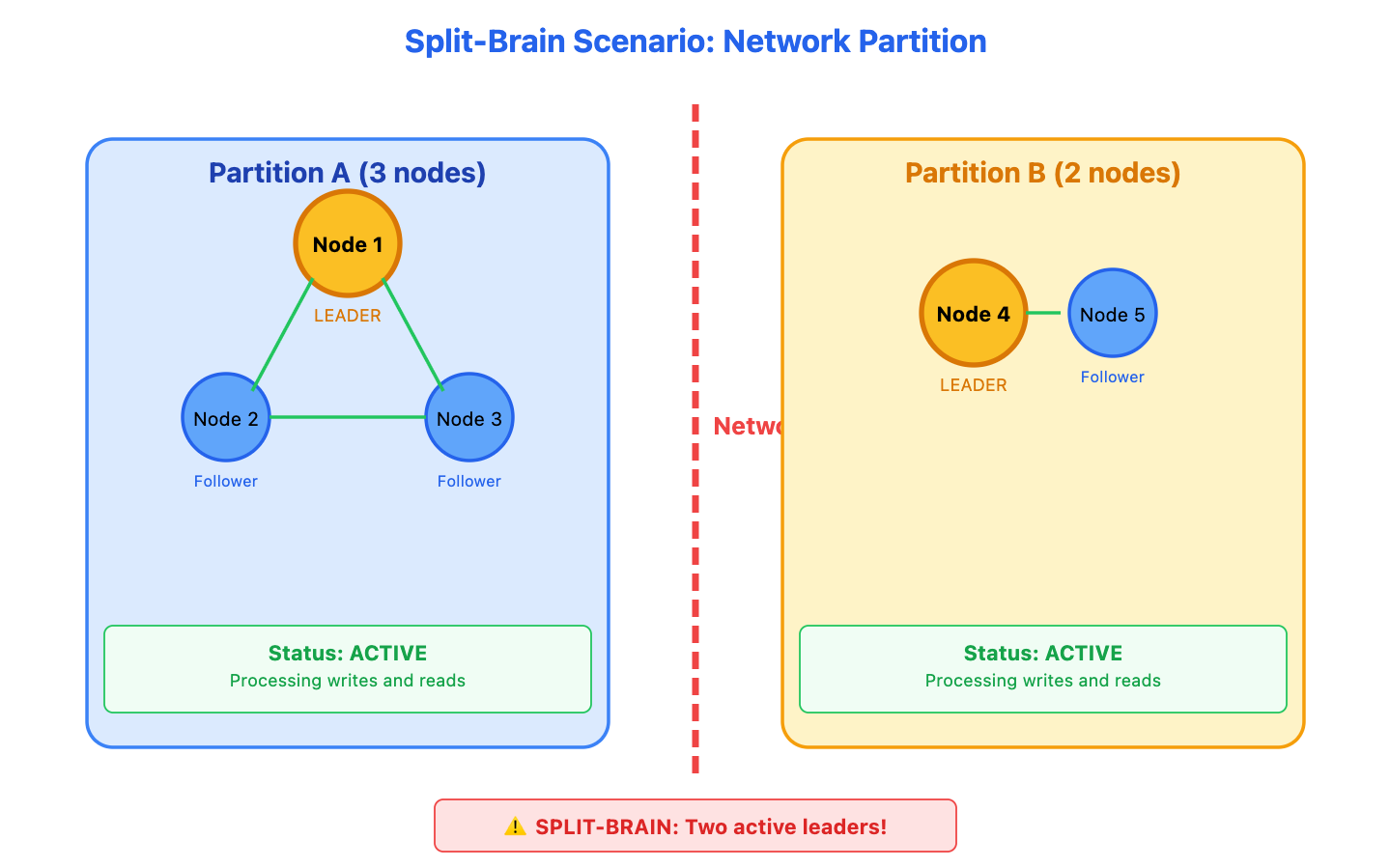

Eventual consistency means that data does not become consistent everywhere immediately. After a change, different parts of the system may temporarily show different states, but over time, they converge to the same correct result.

⚠️ Temporary inconsistency

Example:

- An order is placed.

- The Orders service shows it immediately.

- The Reporting service updates a few seconds later.

- Both end up consistent, just not at the same time.

Why do systems choose eventual consistency?

- Better availability during failures.

- Higher throughput and lower latency.

- Independent scaling of services.

- No distributed locks or 2PC.

How to explain this to the business

Translate technical delay into business behavior. Do not say: "eventual consistency".

Say

some screens may update a few seconds later”

Be explicit:

- Dashboards can lag by minutes.

- Notifications may arrive later.

- Payments and balances must be consistent immediately.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Understands that Read operations might return "stale" data immediately after a Write. Knows that this is a normal part of cloud-scale apps.

- 🎓 Middle: Can design UX patterns to hide latency (e.g., Optimistic UI updates). Knows how to use Idempotency keys to handle cases where a user retries an action because they didn't see the update yet.

- 👑 Senior: Can apply the CAP Theorem to justify consistency choices. Architect the system to ensure Business-critical paths remain strongly consistent while offloading heavy reporting to eventually consistent read models (CQRS).

📚 Resources: Consistency Models for Distributed Systems

❓ What is the difference between logical clocks and physical clocks?

A physical clock is a device that indicates the time. A distributed system can have many physical clocks, and in general, they will not agree.

A logical clock is the result of a distributed algorithm that allows all parties to agree on the order of events.

Examples of physical clocks include a wall clock, a watch, a computer time-of-day clock, a processor cycle counter, the US Naval Observatory, etc.

An example of a logical clock is a Lamport Clock:

class LamportClock

public int tick(int requestTime) {

latestTime = Integer.max(latestTime, requestTime);

latestTime++;

return latestTime;

}Key differences between Physical clocks and Logical clocks

- Physical clocks track real time, logical clocks track order.

- Physical clocks can drift; logical clocks cannot.

- Physical clocks are suitable for logging and UX; logical clocks are ideal for correctness.

- Logical clocks cannot tell you actual timestamps.

Physical clocks are used for:

- Logs and monitoring.

- Expiration times and TTL.

- User-facing timestamps.

Logical clocks are used for:

- Conflict resolution.

- Distributed databases.

- Event ordering.

- Detecting causality.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that physical clocks show time, logical clocks show order.

- 🎓 Middle: Understand clock drift and why ordering cannot rely on time alone.

- 👑 Senior: Choose logical or hybrid clocks when correctness depends on causality.

📚 Resources:

❓ What is write-skew, and how does it appear in distributed systems?

Write-skew is a consistency anomaly in which two concurrent operations read the same data, make independent decisions, and then write updates that, together, violate a business rule. Each write is valid on its own, but the final combined state is wrong.

This usually happens under weak isolation or eventual consistency.

Example:

Initial state:

- Doctor A is on call.

- Doctor B is on call.

Two transactions run at the same time:

- Transaction 1 checks if Doctor B is on call, then removes Doctor A.

- Transaction 2 checks if Doctor A is on call, then removes Doctor B.

Both checks pass. Both writers commit.

Final state: No doctors on call.

The rule is broken, even though no transaction did anything “illegal”.

How to prevent or reduce write-skew

- Move the invariant into a single owner or bounded context.

- Use stronger consistency where invariants matter.

- Model rules as atomic updates rather than read-then-write.

- Use database constraints or conditional updates when possible.

- Accept eventual consistency only where violations are tolerable.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Know that concurrent updates can break rules even if each update looks correct.

- 🎓 Middle: Recognize write-skew in weak isolation and distributed workflows.

- 👑 Senior: Design invariants carefully and choose consistency guarantees intentionally.

📚 Resources:

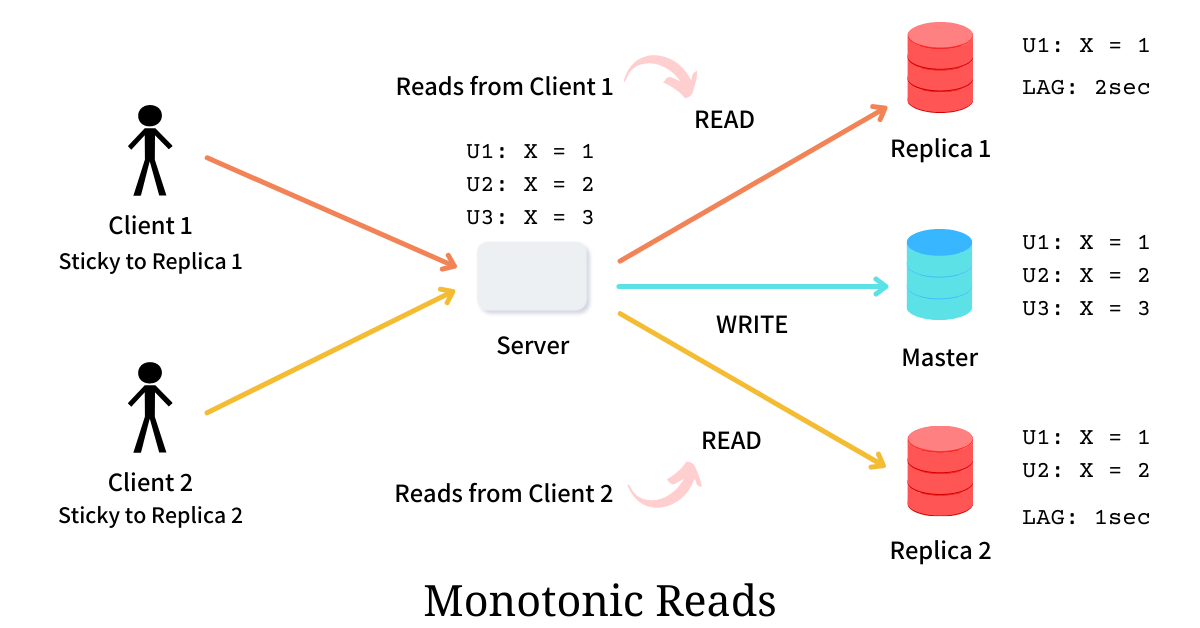

❓ What is monotonic read consistency, and why does it matter?

Monotonic read consistency is a guarantee in distributed systems that once a process has read a specific version of a data item, any subsequent reads by that same process will never return an "older" version of that data.

In simpler terms: Time only moves forward. Even if the system as a whole is eventually consistent, a single user should never see data "roll back" or vanish after they have already seen it.

In eventually consistent systems, data replicas update asynchronously. Without monotonic reads, a client might:

- Read new data from one replica.

- Read older data from another replica later.

Common approaches to achieve monotonic read:

- Session stickiness to the replica.

- Read-your-writes guarantees per user session.

- Client-side version tracking.

- Routing reads to replicas that are at least as fresh as the last seen version.

- This is often done at the platform or database level, not in business code.

What monotonic reads do not guarantee

- They do not guarantee global consistency.

- They do not guarantee the latest data for everyone.

- They only guarantee a stable experience for a single client.

What .NET engineers should know

- 👼 Junior: Ensure users do not see older data after viewing newer data.

- 🎓 Middle: Understand how eventual consistency can break UX without monotonic reads.

- 👑 Senior: Design read paths and session behavior to preserve monotonic guarantees.

📚 Resources: Monotonic Reads Consistency

Resilience and Failure Handling

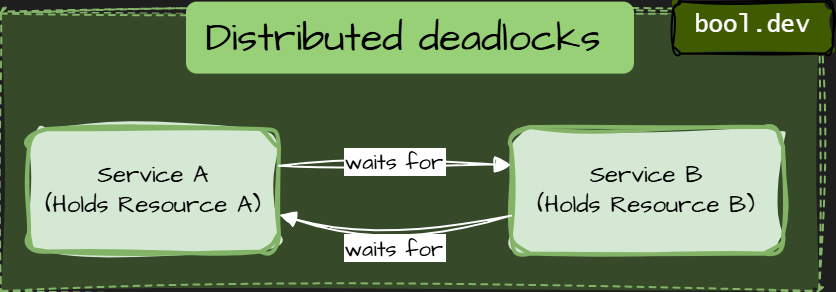

❓ What is a distributed deadlock, and how does it occur?

A distributed deadlock occurs when multiple services or nodes in a distributed system wait for each other indefinitely, preventing any of them from making progress. Each participant is blocked, waiting for another to release a resource, respond, or complete an action.

Types of distributed deadlocks:

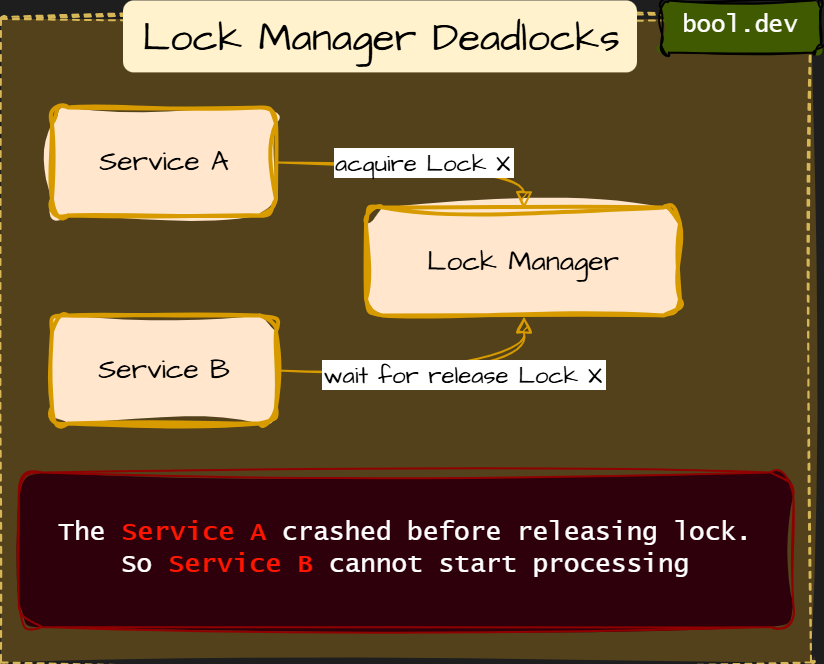

Resource-Based Deadlocks

Resource-based deadlocks are the most common type of distributed deadlock. They happen when services hold exclusive resources and wait for other resources owned by another service.

How to prevent resource-based deadlocks

- Never hold locks while making synchronous remote calls. Commit or release resources before calling another service.

- Define a global resource ordering. If multiple resources must be locked, always lock them in the same order across services.

- Reduce lock scope and duration. Short transactions. Minimal critical sections.

- Prefer async workflows for cross-service coordination. Events and message queues break circular waiting.

- Design idempotent operations. So retries do not extend lock lifetimes.

- Treat business invariants as resources. If an invariant is exclusive, explicitly design it.

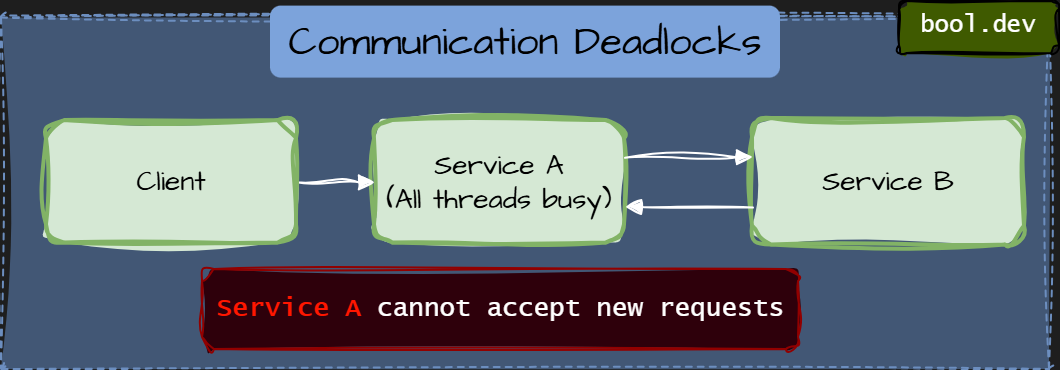

Communication Deadlocks

A communication deadlock occurs when services block each other through synchronous communication, even without explicit locks.

Each service waits for a response from another service, forming a cycle of blocking calls. No database locks. No distributed locks. Just waiting on the network.

How to prevent communication deadlocks

- Avoid synchronous call cycles. No service should synchronously depend on itself through other services.

- A service should never synchronously depend on itself, even indirectly.

- Prefer async communication for workflows. Queues and events break waiting chains.

- Separate inbound and outbound thread pools. So, blocked outbound calls do not block inbound requests.

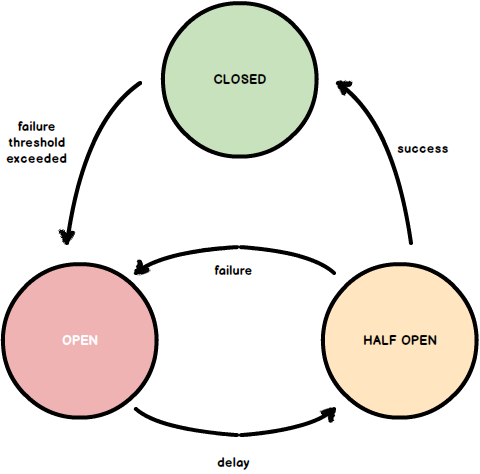

- Set strict timeouts and fail fast. Waiting forever is worse than failing early.